What is vagus nerve stimulation?

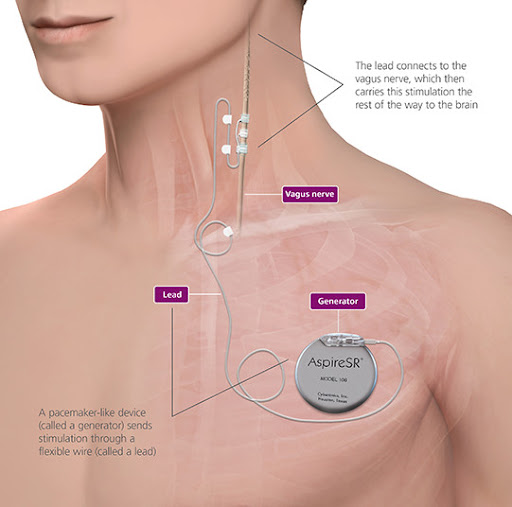

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is a treatment for uncontrolled epilepsy. VNS therapy reduces the frequency and severity of epileptic seizures in some children. VNS therapy involves insertion of a pulse generator, similar to a heart pacemaker, under the skin on the chest that sends intermittent electrical signals to the brain by stimulating the left vagus nerve in the neck. The pulse generator is programmed to stimulate in two ways. It is individually programmed to automatically stimulate in the background, typically ON for 30 seconds and OFF for 3 minutes. In addition, the pulse generator can be manually activated in between programmed stimulation times by the child or caregiver, by placing a provided magnet over the pulse generator and then removing it. This gives extra stimulation at pre-programmed settings.

It is not fully understood how VNS therapy works, but the theory is that the VNS over time modulates nerve pathways involved in seizures. VNS therapy works differently to antiseizure medications and dietary treatments.

Who is suitable for vagus nerve stimulation?

VNS therapy is generally considered for children with epilepsy which significantly affects the life of the child and family, is not adequately controlled by antiseizure medication, and is not treatable with surgery. Assessment by a paediatric neurologist experienced in comprehensive epilepsy management, including surgery, and VNS therapy is a prerequisite.

What does the vagus nerve do?

The vagus nerve is one of the cranial nerves, meaning a nerve that is connected directly to the brain. Output nerve fibres control muscles responsible for swallowing, coughing and voice sounds. Input nerve fibres transmit sensations and electrical feedback from the heart, lung, stomach and upper bowel to the brain. About 80% of the nerve fibres in the left vagus nerve are input fibres transmitting, from the body to the brain, and the output fibres have minimal heart connections, making the left vagus nerve a suitable "wire" into the brain.

History of vagus nerve stimulation

The first VNS device was implanted in 1988 in the United States of America. Regulatory approval as an adjunct therapy in reducing seizure frequency was granted in 1994 in Europe and 1997 in USA. The first implant in Australia was in 1994 and regulatory approval by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia) was granted in April 2000. VNS devices have been implanted in patients for over 25 years. More than 125,000 patients globally have been implanted with VNS devices. In Australia, more than 750 patients have been implanted.

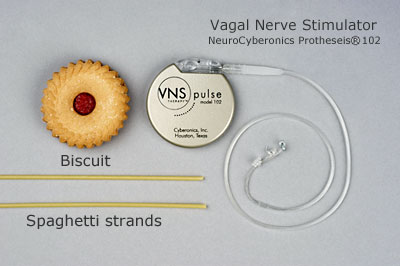

What does a vagus nerve stimulator look like?

.jpg)

What is involved prior to vagus nerve stimulation?

Children require referral from their neurologist or paediatrician to an epileptologist at the RCH for assessment of suitability. The child's seizure history, prior and current treatments, behaviour and past medical problems need to be reviewed. Alternative treatments are also discussed.

Families are fully informed about VNS therapy before embarking on this form of treatment. The epileptologist and the epilepsy nurse specialist discuss realistic expectations of VNS therapy, how VNS works, the surgical procedure, post-operative care, advantages and disadvantages, continuing medication, the admission process and precautions. Families will meet with the neurosurgeon prior to planned surgery.

What happens during the admission for insertion?

The child and family present to the Surgical Admissions reception on the 3rd floor on the morning of surgery. Usual medications are taken unless otherwise instructed by the neurologist. The anaesthetist assesses the child and routine blood tests are performed. Post-operative care is discussed with medical and nursing teams, particularly relating to pain management, oral intake, seizure management, antiseizure medications, and wound care. Parents may accompany their child to the pre-theatre waiting area.

Implantation of the VNS pulse generator and lead wire requires an operation, which usually takes two hours. Children require a general anaesthetic and at least an overnight stay in hospital. Two incisions are made to implant the pulse generator and lead wire, one horizontally on the left side of the chest below the collar bone (clavicle) and one vertically in a skin fold on the left side of the neck. The stimulator with lead wire connection is inserted under the skin on the upper left chest wall. The lead wire is passed under the skin and the contacts are wrapped around the left vagus nerve. The VNS unit is tested prior to skin closure but then left off.

Children are admitted to the Cockatoo Ward following surgery and usually stay in hospital for one or two nights. Fluids and antibiotics are given by intravenous drip for at least 24 hours. Regular assessment of the child's comfort continues throughout the hospital stay and oral pain medications are administered as required. Most children have minimal pain that is controlled by paracetamol. Oral pain medications continue at home as necessary.

The two wound sites are covered with a clear waterproof dressing which allows for normal bathing and easy assessment of the wounds. No stich removal is required, as all stitches dissolve under the skin.

The VNS is turned on 10-14 days post insertion.

The scars will be quite reddened initially and will fade to white with time, depending on individual healing processes. In some people, scars on the chest remain red and may thicken and become raised.

Neurosurgical follow up occurs shortly after discharge from hospital and assessment of wound site will occur at this visit. Regular appointments are scheduled with the neurologist, usually every 4 weeks initially. During these visits, the functioning of the VNS is checked, seizure history noted, and the stimulating parameters increased, as tolerated, towards settings which are usually effective.

Antiseizure medications remain unchanged while titrating the device settings over time, typically for 3-6 months.

The VNS device contains a battery, which lasts between 5-7 years, depending on the programmed output current and frequency of stimulation. Towards the end of the battery life, it is possible to turn VNS therapy off if there has been uncertainty about its effectiveness, to assess if the device needs to be replaced. Otherwise, the device is just replaced.

Does vagus nerve stimulation work?

VNS has been extensively studied in clinical trials around the world, including in children. The results vary depending on the patients studied and the design of the trial.

The following is our summary of the available data:

- About 30-50% of all children gain a significant improvement in seizure control, with reduced seizure frequency or severity

- 65% of patients with the Lennox-Gautaut syndrome have greater than 50% seizure reduction

- Less than 10% of children become seizure free and most continue taking antiseizure medication

- Results are similar across all seizure types and syndromes

- Children with recurrent bouts of seizures that escalate to hospitalisation often benefit from VNS therapy

- Termination of prolonged seizures or seizure clusters is possible in some children

- Currently there is no way to predict response to VNS therapy

- Many children have improvements in mood, alertness and overall quality of life, even in the absence of significant seizure improvement

- Seizure reduction is often not evident for several months

- Over time there may be a continued decline in seizures in many patients. 25% may have a reduction in seizure frequency at 3 months, increasing to 50% after 2 years

- Unlike the effectiveness of some antiseizure medications, benefits of VNS therapy are maintained long-term

What side effects or problems can occur?

- The most common side effects reported with VNS are hoarse voice, pain or tingling in the throat or neck, cough, shortness of breath, headache and ear pain.

- Most side effects only occur during stimulation settings and settle over time or after adjustment of stimulation settings.

- Less common side effects of VNS are difficulty sleeping, weight loss, reduced exercise tolerance, snoring and apnoea during sleep, vomiting, facial flushing, dizziness and irritability

- Swallowing problems and rarely aspiration may occur in some children with physical disabilities, feeding difficulties and reflux

- Wound breakdown, wound infection and device damage are rare but potentially serious complications

- Cessation of heart beat has been rarely reported in adults undergoing VNS implantation, during the intraoperative lead test, but this has not been reported in children

Precautions with vagus nerve stimulation

Physical trauma to the pulse generator or lead wire, such as with rough sport or neck manipulation, can damage the device.

Equipment that may interfere with the stimulator should be avoided. These include strong magnets, hair clippers and loudspeakers. Some medical tests, such as MRI scans, can interfere with the device. Always tell health professionals that your child has a VNS implanted.

The neurologist or epilepsy nurse specialist should always be consulted prior to any medical imaging, diagnostic testing or surgical procedures, to ensure patient safety and device integrity. The pulse generator may need to be turned off temporarily and special precautions may need to be taken with anaesthesia, surgery or scanning.

Always avoid areas where pacemaker warning signs are posted.

The magnet provided for manual stimulation may damage credit cards, mobile phones, computer disks, televisions and other items affected by strong magnetic fields. Care should be taken to store magnet away from these types of equipment.

What is the cost of a vagus nerve stimulator?

Funding for VNS therapy in Australia is complex and varies between states and centres, and between the specific device models. VNS therapy is fully funded at RCH. If specific funding issues apply, these will be discussed by the treating neurologist.

References and links

Commercial links

The following company web site may be useful for further general information regarding VNS therapy. After visiting this site, ask your neurologist if you have questions.

Selected references

Original Controlled Trials of VNS

- Ben-Menachem E et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment of Partial Seizures: 1. A Controlled Study of Effect on Seizures. Epilepsia 1994; 35: 616-26.

[PubMed]

- Ramsey RE et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment of Partial Seizures: 2. Safety, Side Effects, and Tolerability. Epilepsia 1994; 35: 627-36.

[PubMed]

- George R et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Treatment of Partial Seizures: 3. Long-Term Follow-Up on First 67 Patients Exiting a Controlled Study. Epilepsia 1994; 35: 637-43.

[PubMed]

- The Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. A randomized controlled trial of chronic vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of medically intractable seizures. Neurology 1995; 45: 224-30.

[PubMed]

- Ben-Menachem E et al. Evaluation of refractory epilepsy treated with vagus nerve stimulation for up to 5 years. Neurology 1999; 52: 1265-7.

[PubMed]

VNS Studies in Children

- Murphy JV et al. Adverse Events in Children Receiving Intermittent Left Vagal Nerve Stimulation. Pediatr Neurol 1998;19:42-3.

[PubMed]

- Parker APJ et al. Vagal Nerve Stimulation in Epileptic Encephalopathies. Pediatrics 1999; 103:778-82.

[PubMed]

- Murphy JV and the Pediatric VNS Study Group. Left vagal nerve stimulation in children with medically refractory epilepsy. J Pediatrics1999;134:563-6.

[PubMed]

- Frost M et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in children with refractory seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia 2001;42:1148-52.

[PubMed]

- Nagarajan L et al. VNS therapy in clinical practice in children with refractory epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand 2002;105:13-7.

[PubMed]

- Helmers SL et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and costs associated with implantation of vagus nerve stimulation therapy in pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2012;16:449-58. [PubMed]

- Orosz I et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for drug-resistant epilepsy: a European long-term study up to 24 months in 347 children. Epilepsia 2014;55:1576-84. [PubMed]

Reviews of VNS

- Boon P et al. Cost-benefit of vagus nerve stimulation for refractory epilepsy. Acta Neurol Belg 1999;99:275-80.

[PubMed]

- Valencia I et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in pediatric epilepsy: a review. Pediatr Neurol 2001;25:368-76.

[PubMed]

- Ben-Menachem E. Vagus-nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Lancet Neurology 2002;1:477-82.

[PubMed]