See also

Autism and developmental disability: Management of distress/ agitation

Key points

- Management should focus on verbal and non-verbal de-escalation; emphasise the child's safety and use existing behaviour or communication plans where appropriate

- Consider if the child has an underlying neurodevelopmental condition or history of adverse childhood experiences

- Consider and exclude organic causes including pain, encephalopathy or delirium

- Pharmacological treatment may be required to ensure the safety of the child and staff

- Physical restraint is a last resort, only used to facilitate rapidly effective pharmacological treatment by appropriately trained staff

Background

- Behavioural distress and its underlying causes are different in children compared to adults

- The most important initial action is to reduce the child’s distress to reduce the behaviour and risk of harm

- Once the distress has been addressed, further assessment and specific management of the underlying cause should occur

- Behavioural distress can present and progress in a variety of ways. There are many predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors to consider in de-escalation strategies

Assessment

History

- Previous episodes and what constructive management was used

- Underlying neurodevelopmental conditions, intellectual disability, communication barriers or any mental health concerns

- Pre-existing behaviour management plans, communication aids or sensory considerations

- History of adverse childhood experiences which may impact on the flight-fight-freeze response. Children may appear calm when in a frozen or dissociated state

- Details of the current episode eg recent health, triggers, life changes or precipitating events

- Consider if the child is in pain

- Current and previous medications and any adverse reactions

- Consider intoxication with alcohol, illicit drugs or prescribed medication

Examination

- Briefly exclude obvious focal neurology, acute pain, altered conscious state or evidence of a toxidrome

- A more comprehensive examination should occur once level of distress is reduced

Management

| Approach to de-escalating behavioural disturbance |

Aims |

- Verbal and non-verbal de-escalation is the first line intervention

- Treat the underlying causes

- Involve senior staff early and consider the need for a Code Response

- Debrief the child, family and staff

|

Environment |

- A private, calm, quiet room with soft lighting. Eliminate triggers for agitation

- Family member presence should be considered on case-by-case basis

- Remove dangerous items, be aware of exits and ensure own safety

|

Child |

- Respect personal space

- Consider child's individual needs including language, neurodevelopmental conditions, cognitive ability or trauma history

- Consider where age-appropriate, distraction techniques, familiar toys, communication aids and objects

- Consider physical needs and offers of analgesia, food, drink etc

- Anticipate and identify early escalating behaviour

- Consider involving mental health expertise early

- Offer planned 'collaborative' sedation eg ask the child if they would take oral medication where appropriate

|

Staff/Self |

- Ensure all staff have an aligned plan before approaching child

- One staff member communicates with the child and family

- Introduce self, emphasise collaboration with child

- Minimise behaviours and interventions that the child may find provocative

- Use concise non-judgemental language and set expectations in a calm voice (eg focus on one idea at a time, active listening, especially regarding the child’s goals)

- Provide an opportunity for child to regain control of their emotions

- Set clear limits on behaviour for child and family

- Avoid bargaining, but offer clear choices and negotiate realistic options

- Maintain professionalism at all times. Ignore insults and challenging questions

|

Investigations

Investigations are not routine but may be necessary to exclude organic causes of altered conscious state

Treatment

Providing a safe environment to calmly de-escalate a child without the use of physical restraint is the priority

Possible need for sedation

Consider oral or intramuscular sedation only if de-escalation strategies are unsuccessful or there are concerns for safety

Consent

- Obtain consent (ideally from child and/or guardians) for any medical procedures, including sedation, wherever possible

- Common law recognises that a young person can give consent if they have capacity

- In an unsafe situation, when the child is a danger to themselves or others, no consent is necessary, but clinicians should be aware of the relevant duty of care and Mental Health Act in their jurisdiction (see Additional notes below)

After appropriate assessment, a child who does not need acute medical or psychiatric care should be discharged from the hospital to a safe environment, rather than be chemically or physically restrained

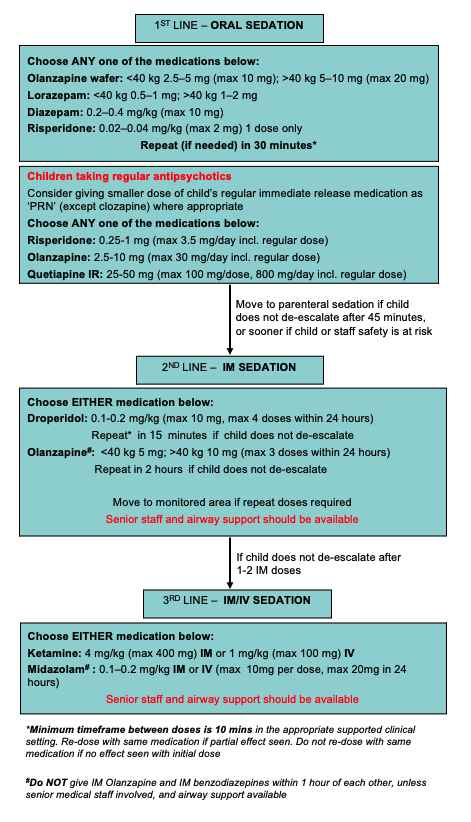

Acute behavioural disturbance medication flowchart

For use when non-pharmacological management has been ineffective

A stepwise approach should be used if pharmacological treatment is required, but always consider child and staff safety, and whether more rapid escalation is needed

Medication Adverse Reaction Table

|

Medication |

Side effects |

Management |

|

Respiratory depression |

Extra pyramidal reaction |

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome |

Paradoxical reactions |

|

Benzodiazepines |

✔ |

– |

– |

✔* |

Airway support

Consider Flumazenil** |

Typical antipsychotics (Droperidol) |

If used with opioids |

✔ |

✔ |

– |

Benzatropine 0.02 mg/kg (max 1 mg) IV or IM

Repeat in 15 min if required |

Atypical antipsychotics (Olanzapine, Quetiapine, Risperidone) |

✔ |

✔

(fewer) |

✔ |

– |

Benzatropine 0.02 mg/kg (max 1mg) IV or IM for olanzapine-associated dystonic reactions

Repeat in 15 min if required |

Ketamine |

With rapid administration |

– |

– |

– |

Airway support |

*Paradoxical reactions, such as increased agitation and anxiety, may occur in children with autism or developmental delay

** Do not give to child taking frequent or long-term benzodiazepines or to a child who may have taken substances associated with causing seizures. Always involve senior staff

Post-sedation monitoring

- Monitoring should be performed in a safe environment within the clinical setting, assessing for side-effects as listed above

- Do not unnecessarily wake or irritate the child further to permit sufficient rest

- Consider using an appropriate local sedation assessment scale

- An alert child should have 30 minutely observations for 2 hours post sedation medication

- An agitated child needs continuous clinical observation and regular vital signs

- A child with altered conscious state should have 1:1 clinical support, continuous pulse oximetry and regular medical review

- Following medication, the child must undergo a medical and mental health assessment to guide subsequent management

Code response

If de-escalation strategies (above) are unsuccessful or there are any safety concerns, a Code Response may be required with an appropriately trained team. See local guidelines

Documentation

Include:

- Reasons for sedation

- Medications used, dose and route

- Which interventions (including non-pharmacological) were used, which were effective and which were unsuccessful

- Additional documentation may be required to address:

- Code Response

- Patient safety/local risk incident reporting system

- Staff safety/OHS

- Consent

- Mental Health Act (see Additional notes below)

- Restraint Register (NSW)

Defusing and debriefing

- The management of a behaviourally distressed child can be extremely difficult for staff involved

- A critical incident stress debriefing session is encouraged

- Support child and family following the event to build an ongoing therapeutic relationship and prevent future distress

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- The child requires admission for treatment of a medical problem causing behavioural disturbance, or for observation until drug toxicity has resolved

- Local mental health clinicians are involved in the ongoing care of behaviourally distressed children

Consider transfer when

- The child requires a tertiary inpatient mental health facility or ongoing care (to be facilitated by local mental health clinicians)

- There are complications from sedation

- The care required is beyond the comfort level of the hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric transfers, see Retrieval Services

Consider discharge when

- Behavioural distress has reduced or resolved

- Significant medical or psychiatric illness is excluded and/or addressed

- Any identified underlying cause has been treated

- Carers are capable of and willing to take the child home; consider crisis care where required

- A clear plan for medical and/or mental health follow-up is in place

Parent information

Challenging behaviour – school aged children

Challenging behaviour – teenagers

Disruptive disorders in children. What we should know as parents

Mental health – adolescents

Additional notes

Restraint in Mental Health Acts Across Australia

Restraint in Australian and New Zealand Mental Health Acts

Interstate guides to informed consent and the Mental Health Acts:

NSW

Mental Health Act 2007 No 8

Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 No 157

Queensland

About the Mental Health Act 2016 – Queensland Health

Guide to Informed Decision-making in Health Care 2nd Edition – Queensland Health

South Australia

Mental Health Act 2009

Victoria

Mental Health and Wellbeing Act 2022 Handbook

Chief Psychiatrist’s guidelines regarding restrictive intervention

Informed consent

Western Australia

WALW - Mental Health Act 2014

Chief Psychiatrist’s Guideline on the Use of Detention and Restraint in Non-Authorised Healthcare Settings, Chief Psychiatrist Government of Western Australia

Chief Psychiatrist, Government of Western Australia

Last updated December 2024