See also

Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute Management

Acute Behavioural Disturbance: Code Response

Key points

- The parents, carers and/or child should be able to advise on what techniques have previously worked well to minimise distress

- Maintain a low stimulus environment wherever possible

- Assume the child with acute distress may have an underlying medical issue, until proven otherwise. Repeated examinations may be required

- Avoid unnecessary distress through repeated interventions (eg venepuncture) and plan thoroughly ensuring all investigations are performed together

Background

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition features of which become evident in early childhood, affecting the way the person communicates and interacts with their environment

- Children and teenagers with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities are 10 times more likely to be admitted to hospital for medical illnesses and complaints. They can be more difficult to assess because they communicate differently and may not tolerate an unfamiliar clinical environment

- Behavioural and communication difficulties act as significant barriers to these children accessing hospital care. Children with autism and intellectual disability (ID) have a higher incidence of behavioural problems compared with children who have ID without autism

- Behavioural concerns can include meltdowns, self-injurious behaviour and aggression. This may indicate an underlying physical illness causing pain, emotional dysregulation, anxiety or communication difficulty, perhaps in relation to intolerance of change. The underlying cause should be investigated

- Children and teenagers with ASD, ID and other developmental disabilities have the same rights of access to health care and should be treated with the same dignity, respect and understanding shown to typically developing patients

Autistic children may exhibit:

- Impaired social communication and interaction, such as deficits in social-emotional reciprocity and decreased non-verbal communication. Consider speaking in short sentences, using fact-based, rather than feeling-based communication

- Restrictive, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities, including stereotypies, highly fixated routines and inability to cope with sudden changes to routine. Routines enable young people with developmental disabilities to manage their internal states of distress. Similarly, changes in routine (eg acute or planned hospitalisation) can cause significant stress and distress

- Sensory sensitivities to loud or unexpected sounds, light, colours, textures, smells and/or touch. Children may be hyper-sensitive or hypo-sensitive to these stimuli. These may trigger agitation but knowledge of these sensitivities may allow preventative measures to be put in place. Consult with parents or carers regarding sensory stimuli to avoid or those that may soothe the child

ASD can be associated with other neurodevelopmental comorbidities, including speech and language disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and ID

ASD can also be associated with psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorder

Assessment

History

The child has presented due to a change from their baseline. Utilise family members to interpret the child’s behaviour and look for an underlying cause

Useful questions to ask parents and carers

- Is there anything immediate we can do to help your child?

- What was your child’s last visit like?

- How can we make this visit easier for you and your child?

- How would we know if your child is in pain?

- How can we best comfort your child?

- How does your child express their needs/desires?

- How does your child say yes/no?

- How does your child generally comprehend communication – verbal/non-verbal/visual?

- What would help us communicate with your child?

- What type of toys or activities does your child prefer?

- Does your child have difficulty with transitions? If so, what tends to help?

- Has your child had previous procedures? If so, which techniques were helpful or not helpful?

- Does your child respond to visual cues? Would a video or picture example of a procedure help?

Acute presentation

- Determine if this has occurred previously, and how it was managed

- Identify any potential triggers for the acute distress

- Is the child otherwise well? Check their observations

- Consider underlying pain. How does the child respond to pain whilst being examined?

- Consider changes to diet

- Assess fluid balance

- Look for potential sources of infection

- Consider changes in bowel habit, particularly constipation

Examination

It is important to look for the cause of an acute episode of distress or agitation. Consider pain or underlying physical illness as possible contributors

- This cohort of children may have higher pain thresholds

- Examine opportunistically

- A careful assessment is required. Examine and re-examine again until a cause is identified

- Communicate with the child before each step of the exam

Management

Investigations

Consider basic investigations to look for a medical cause of an acute presentation, as indicated based on history and examination. Aim to minimise distress by performing all relevant investigations together

Treatment

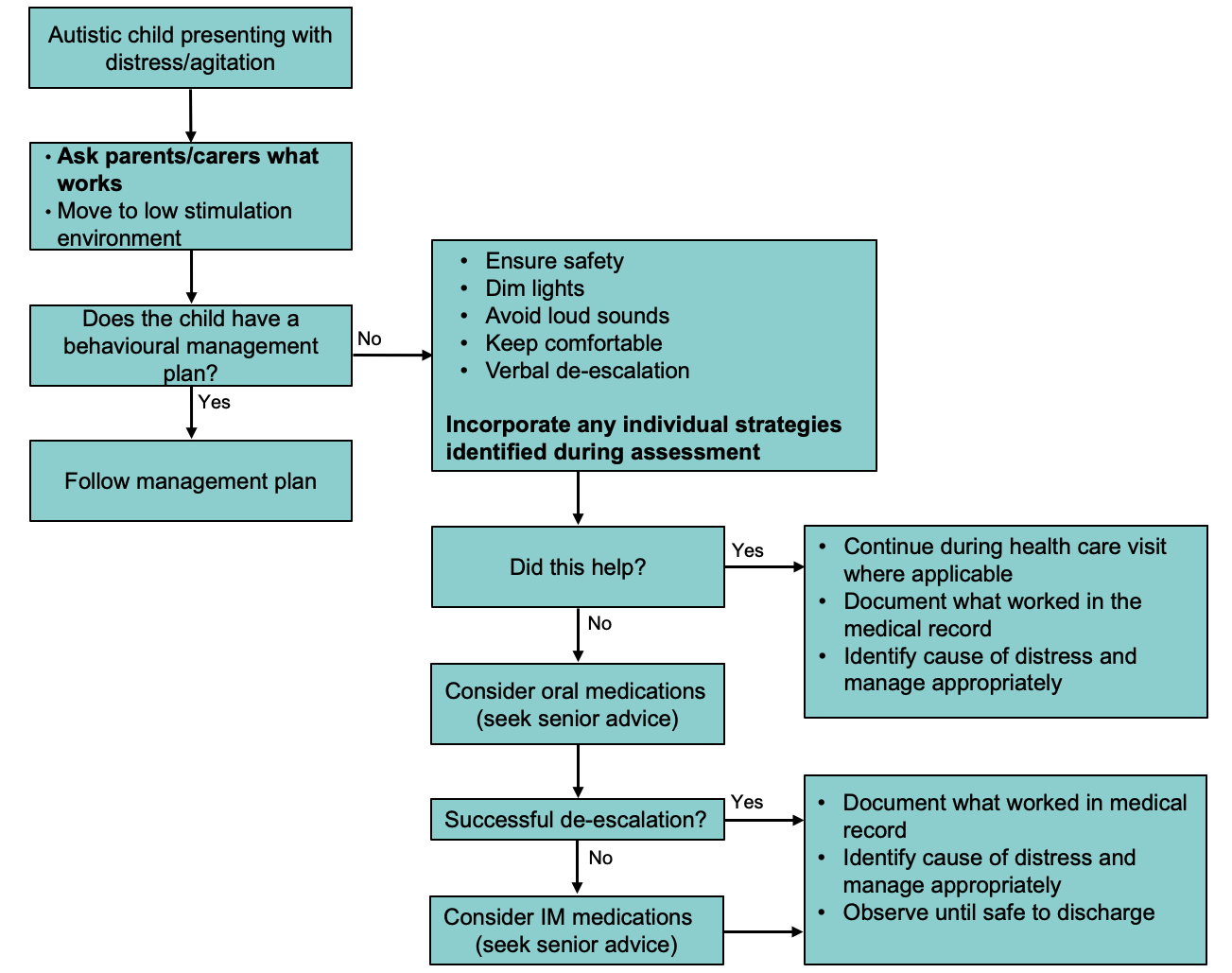

Once identified, autistic children presenting with difficult behaviours should be moved to a low-stimulus environment (if possible). Note that the patient may have an existing Behavioural Management Plan with advice on how to manage acute distress

For acute presentations see Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute management

Environmental modification

- Maintain a low stimulus environment, with dim lighting and minimise loud sounds

- Ensure familiar faces (parents or carers) are close by

- Minimise the number of staff entering the patient’s environment

- Attempt to make the environment as familiar to the child as possible, with the child's own toys, bed sheets and pillows, if possible

- Use music and technology that the child is familiar with, if these are helpful

- Use appropriate sensory toys to distract the child

Plan ahead for procedures

- Use Child Life (Play) Therapy techniques and staff early

- Explain any procedures to the child, in a form they can understand (eg use visual cards, photos, sign, gesture or simple instructions)

- Demonstrate what you are doing on a parent or carer (eg auscultation, using thermometer)

- Aim to minimise intervention, with all necessary investigations performed in the same procedure or under the same sedation, if required

- Have the child sit with their parent or carer for the procedure, if practicable

- Use distraction techniques

- Where possible, remove the IV cannula whilst the child is sedated to minimise distress caused by removing it later

Psychotropic medication can be used in the non-acute pre-emptive management of agitation or anxiety during hospital visits or before procedures

When considering the type of medication consider the following:

- Child’s current medications (with specific attention to drug-drug interactions)

- Contraindications in the medical and behavioural history, and individual-specific challenges

- Specific procedure/visit considerations (eg invasiveness, duration)

See Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute management flowchart

Once distress is managed, ensure to look for an underlying cause. If no medical cause is identified and there are ongoing concerns, consider a mental health referral

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Initial strategies are unsuccessful

- Cause of agitation is not clear, despite investigation

- Child requires admission for monitoring post-sedation

- Child requires further investigation of cause of acute distress

Consider transfer when

Child requires care beyond the comfort level of the local hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services

Consider discharge when

The child is back to their baseline post any sedation, and the cause of their acute distress has been identified and appropriately managed (if applicable)

The child should have appropriate follow up from their treating outpatient clinician or General Practitioner

Parent information

RCH Kids Health Info fact sheets on challenging behaviour:

Additional notes

Management of patients with acute behavioural disturbance (health.qld.gov.au) guideline

RCH specific guidelines:

Code Grey procedure (RCH intranet)

Last updated June 2022