See also

Trauma - the primary survey

Head injury

Thoracic elevation device

Key Points

- Cervical spine injury (CSI) is uncommon in children

- Allowing excessive movement of an unstable CSI may lead to severe morbidity

- Most cervical spines can be cleared clinically. A senior clinician must assist in the assessment of children with persistent symptoms or who are unable to communicate

- Foam collars are recommended (if the child will tolerate one) until CSI can be excluded. Hard collars have no proven patient benefit and are potentially harmful

Background

This guideline is for cervical spine assessment only

- Cervical spine assessment and the detection of CSI is difficult. Avoid unnecessary immobilisation and imaging where possible

- A validated clinical decision rule for the paediatric population does not exist. This guideline is designed to assist and empower the clinician to:

- clear the cervical spine in children who have sustained blunt trauma

- order imaging where appropriate

- identify the cases where expert spinal services are required

Spinal Precautions

The aim is to minimise movement of the potentially injured spine.

Ideally the spine should be kept in a neutral position with the child lying flat.

In a child under 8 years old this may be achieved by a

thoracic elevation device and in a teenager head elevation device may be used

Assessment

History

High risk mechanism of injury

- Axial load to the head (diving, trampoline, falling from height)

- Forced neck hyperflexion (includes low velocity mechanism with high force eg rugby scrum collapse)

- Ejection from a vehicle including motorbike

- Improper restraint in a motor vehicle collision (MVC)

- Passenger in an MVC of >60 km/hr, head on collision, rollover, or any accident with a passenger death

- Pedestrian vs vehicle

- Fall >3 metres (or twice the patient’s height)

- Kicked by, or fall from, a horse

- Substantial torso injury

History of conditions known to predispose to CSI

- Previous cervical spinal surgery

- Trisomy 21

- Osteogenesis imperfecta, Achondroplasia

- Other rheumatological, genetic or metabolic conditions

Persistent symptoms: pain, paraesthesia, weakness

Examination

Red flag features in red

Minimise movement of the potentially injured cervical spine, until the cervical spine is adequately assessed, and a targeted neurological examination performed

For an adequate examination a child must be awake and assessable. This includes:

- being alert and cooperative

- not significantly affected by alcohol or recreational drugs

- not heavily sedated by analgesia or sedatives

- be developmentally able to engage in the assessment process and maintain focus throughout the assessment

Concerning examination findings

- Traumatic torticollis

- Child uses hand to support head or neck (this may be the only sign of an atlanto-occipital dislocation)

- Concerning neurology: objective anatomical motor or sensory deficit. Subjective, transient or improving motor and sensory impairments are less concerning

- GCS

<15

- Cervical spine tenderness or significant neck pain

- Restricted neck movement

- Significant head, chest, abdominal or pelvic injuries (ie those that require admission, investigations or surgery)

- Unexplained refractory hypotension (as a feature of spinal shock)

Examining the cervical spine

Prior to palpation, ask the patient if they have symptoms using age appropriate questions

- Provide reassurance and analgesia

- Whilst minimising neck movement, gently palpate the posterior midline of the neck. Feel from the nuchal ridge to the 1st thoracic vertebra. The most prominent spinal process arises from the C7 vertebra

- Repeat the process lateral to the midline on both sides

- Tenderness may indicate vertebral or soft tissue injury

- If there is no significant tenderness and no abnormal neurology assess the active range of movement of the neck by asking the patient to slowly rotate their head 90 degrees to each side, place their chin to chest and to look up. Stop immediately if this causes pain or paraesthesia and minimise movement of the cervical spine

Children who are unable to communicate

- Should be assessed with assistance from a senior clinician

- Assessment is performed when the patient is awake and alert by allowing the child to freely move their neck whilst they are observed carefully for restricted movement(s) or torticollis

- If the child demonstrates pain free and normal neck movement, the cervical spine can be cleared

Management

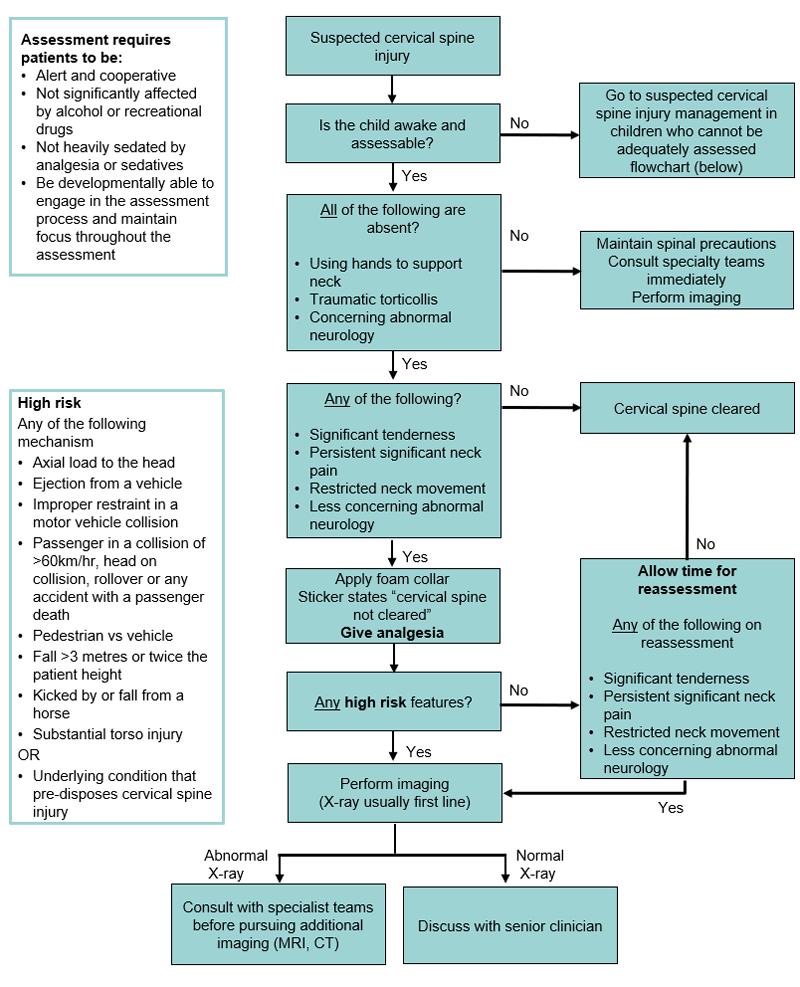

Suspected cervical spine injury assessment & management

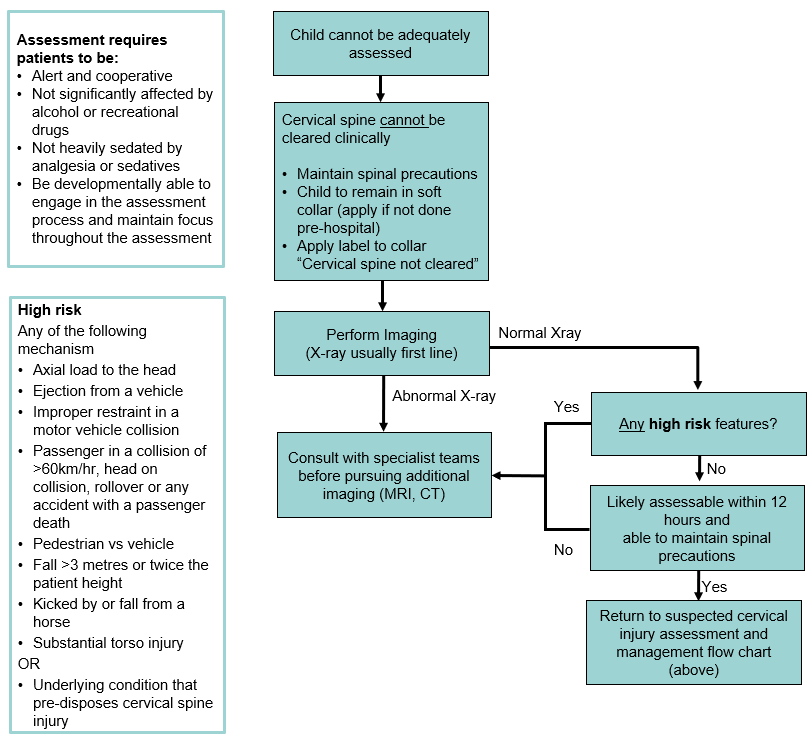

Suspected cervical spine injury management in children who cannot be adequately assessed

Footnotes

| Assessing neurology |

Neurological examination in cervical spine injury is very important, however examination can be difficult due to pain, age or developmental state of the child and altered conscious state

Concerning neurology: objective motor neurology or objective anatomical sensory alteration

Less concerning neurology: transient/improving or subjective sensory impairment which is varying and improving |

|

Conditions pre-disposing to cervical spine injury |

Trisomy 21, osteogenesis imperfecta, achondroplasia, and other rheumatological, congenital, metabolic or genetic conditions or previous cervical spine surgery are known to pre-dispose to cervical spine injury |

|

Senior review |

The senior reviewing clinician should make a decision based on mechanism of injury, their own examination and assessment of the patient, along with any imaging available.

The range of options available, depending on centre and resources available include:

- clearance of the cervical spine and subsequent discharge

- application of a semi-rigid collar (eg AspenTM) with outpatient follow up

- referral for consultation with either orthopaedics or neurosurgery from the ED

|

Restriction of cervical spine movement

Most patients should have movement of the cervical spine minimised using a foam collar labelled with “C-spine not clear” until CSI has been excluded. However, the following three types of patients should be left in a position of preference — do not reposition the neck:

- Children who use their hands to support the head

- Children with traumatic torticollis

- Concerning abnormal neurology on examination

- If a child is fitted with a collar pre-hospital assess as per

flowchart

- Hard collars are not recommended. There is no evidence of definitive improved patient outcome. Potential harm associated with hard collar use includes raised intracranial pressure, respiratory disturbance, patient agitation and soft tissue ulceration

- All children should be removed from spinal boards at the time of transfer from an ambulance trolley

- A

thoracic elevation device (TED) should be used in children under 8 years old when available or head elevation in teenagers to achieve neutral position (see

Spinal Precautions)

- Sandbags or foam blocks can be used but should NOT be taped

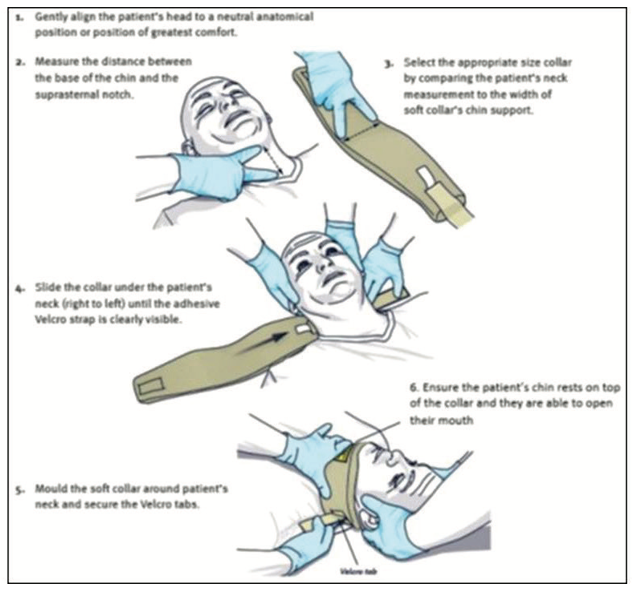

How to apply a soft (foam) collar

Image used with permission from Queensland Ambulance Services (QAS)

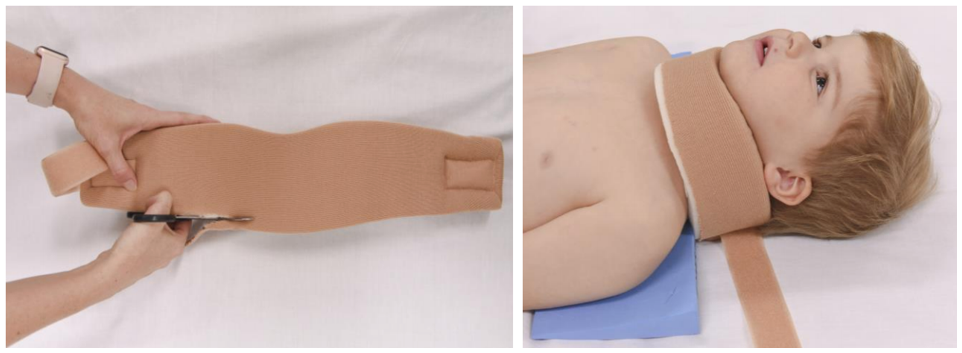

Images used with permission from Children's Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service

- Restrict movement of cervical spine manually

- Patients who are fitted with a pre-hospital collar should be fitted with a new foam collar labelled with “Cervical spine not cleared”

-

Image used with permission from QAS

- Cut along the lower edge of the foam collar to ensure it fits snugly below the chin.

- Provide regular analgesia and reassurance

- Caution should be exercised during moment of risk (

Appendix 1)

If the patient is uncooperative or too small to fit a foam collar (baby or infant) movement should be minimised without the use of a foam collar, as best as possible. It should be made clear to all staff and family that the cervical spine is not clear.

*NB — in young children a collar may cause agitation and potential harm. Distraction of the child and a hands-off technique (eg using a child’s car seat) may be superior to maintain the neck in a position of comfort

Investigations

X-rays (see

flowcharts)

- Child ≤ 5 years old: AP and lateral X-rays only

- 6 years or older: AP, lateral and odontoid X-rays are required

- Lateral X-rays should include views of the vertebral column from the occiput to T1 vertebra (this may require shoulder traction)

- Flexion and extension views are NOT recommended

If X-ray findings are inconclusive or the child has persistent symptoms (regardless of the imaging findings), the foam collar should not be removed and additional imaging (MRI, CT) or review should be considered. Consult the senior clinician and/or specialist teams (eg orthopaedics, neurosurgery)

CT Scans

Consider as first-line investigation after discussion with senior clinician +/- specialist team in patients with highly concerning mechanisms or clinical features such as persistent focal neurological signs, altered level of consciousness, or when a child requires CT scan of additional body areas.

Consider consultation with local specialist teams when

- The cervical spine cannot be cleared clinically

- The role and modality of imaging to investigate suspected CSI is uncertain

- The radiology findings are normal but the child has persistent symptoms or signs

Note: provision of spinal services varies by region, utilise appropriate local or tertiary specialist teams as available

- Where the suggested specialist team is not available locally the patient can be discussed with the appropriate tertiary referral hospital for advice on management

Consider transfer when

- All children meeting major trauma criteria, including suspected or confirmed CSI should be referred and transferred to a major trauma service for definitive management. This should be done in consultation with local state pre-hospital and inter-hospital trauma transfer guidelines

- child requires care beyond the comfort level of the hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see

Retrieval Services

Consider discharge when

- The cervical spine has been cleared

- The cervical spine has not been cleared but both a discharge and follow-up plan has been created in liaison with appropriate local specialist teams (eg orthopaedics, neurosurgery)

Parent information

Head injury – general advice

Head injury – return to school and sport

Hard collar

NSW Foam Collar Report

Appendix: Moments of Risk

|

Moment of risk |

Strategies to protect cervical spine |

|

Trolley transfers & log roll |

Use PAT slide and have one nurse or doctor dedicated to the head & spine

If

<8 years old, use Thoracic Elevation Device on arrival |

|

Pain/agitation |

Early pain relief

Positioning caregiver at head of bed to allow direct eye contact and touch

Attendant to reassure and advise family of how to support the child

In conscious infants consider removing collar and allowing child to find their own best neck position (eg in parent's arms) |

|

Vomiting |

Early administration of antiemetics

(or nasogastric if appropriate) insertion

Attendant or parent present and "nurse call" for log roll if vomiting |

|

Imaging |

Attendant to:

- Accompany to X-ray if removal of collar or manual re-positioning is required

- Ensure TED used appropriately

- Ensure CT head and neck position maintains neck neutrality

|

|

Intubation |

Specific attendant assigned to neck positioning

Consider fiberoptic intubation

Avoid unpredictable muscular contractions eg depolarising neuromuscular junction blockade agents |

Last Updated July 2020