See also

Acute upper airway obstruction

Assessment of severity of respiratory conditions

Inhaled foreign body

Minimising distress in healthcare settings

Key points

- Minimise distress to the child, as this can worsen upper airway obstruction

- Involve senior staff early and consider transfer if concerns regarding worsening upper airway obstruction

- For severe and life-threatening croup, use nebulised adrenaline and seek a skilled senior clinician for airway support

- Less severe cases can be managed with corticosteroids alone

Background

- Croup is inflammation of the upper airway, larynx and trachea, usually triggered by a virus, most commonly parainfluenza as well as other respiratory viruses including COVID-19 (apply appropriate infection control)

- Occurs generally between the ages of 6 months and 6 years

- Often worse at night

Assessment

Children with croup should have focused examination so as not to upset them further:

- Observations such as oximetry and blood pressure are not necessary for managing croup, and can be omitted if expected to cause distress

- Throat examination is rarely required

- Keep child with carer and involve the carer in assisting with examination

History

Risk factors for severe croup include:

- History of previous severe croup

- Pre-existing narrowing of upper airways

- Reduced airway tone due to pre-existing conditions eg trisomy 21, neuromuscular conditions

- Young age: uncommon in under 6 months old, rare in under 3 months old. Consider alternative diagnosis

Examination

- Barking cough

- Stridor

- Hoarse voice or cry

- May have associated widespread wheeze

- Increased work of breathing

- May have fever, but no signs of toxicity

Assessment of severity Loudness of stridor is not a good indicator of severity of obstruction. Soft stridor in the presence of worsening clinical picture may be a sign of imminent airway obstruction |

|

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

Life-threatening |

Appearance/colour |

Normal, well-perfused |

Normal, well-perfused |

Pale |

Pale, mottled or cyanosed |

Behaviour |

Alert and active |

Alert and active, intermittent mild agitation |

Increasing agitation, drowsiness |

Confused, drowsy, agitated

May be not moving, drooling |

Stridor |

None, or only when active or upset |

Intermittent at rest |

Persistent at rest,

or biphasic |

Biphasic or may be soft |

Respiratory rate |

Normal |

Increased |

Marked increase or decrease |

Abnormal, signs of impending respiratory exhaustion |

Accessory muscle use |

None or minimal |

Intercostal and subcostal recession, tracheal tug |

Abdominal breathing, marked intercostal and subcostal recession, tracheal tug |

Severe sternal recession, exhausted, poor respiratory effort |

Oxygen saturation |

Normal |

Normal |

Hypoxia is a late sign which may indicate imminent complete upper airway obstruction |

Differential diagnosis

See Acute upper airway obstruction

- Anaphylaxis

- Inhaled foreign body

- Bacterial infection

- Retropharyngeal abscess

- Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy)

- Bacterial tracheitis

- Epiglottitis

- Airway burns or trauma

Management

Investigations

Croup is a clinical diagnosis. Investigations such as respiratory swab or nasopharyngeal aspirate, X-rays and blood tests are not indicated in typical presentations. Consider appropriate investigations if there is concern for differential diagnoses as above

Treatment

- Minimise distress to avoid worsening symptoms, minimise interventions including examination and investigation that are not going to impact acute management

- Keep child with carers to reduce distress

- Try to keep the environment quiet, moderate lighting

- Children will adopt a position of comfort that minimises airway obstruction, do not change this

Supplemental oxygen is not usually required. If needed, manage as severe upper airway obstruction or consider alternative diagnosis eg anaphylaxis, asthma

Medication

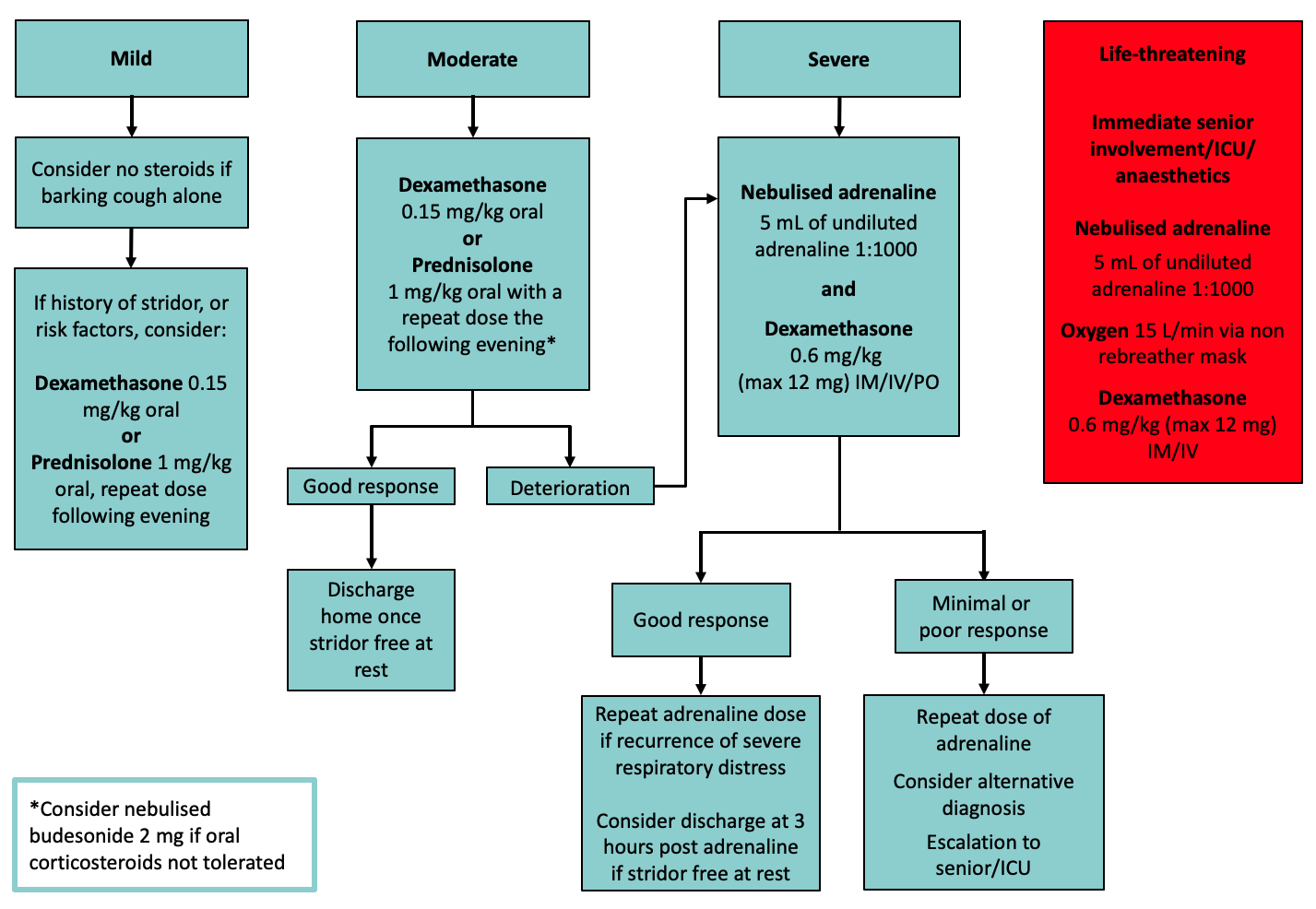

- Mild

- Children with barking cough alone and no history of stridor do not require steroids

- Consider oral steroids: dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg oral or prednisolone 1 mg/kg oral if stridor present or if risk factors such as young age and ability to access urgent review

- Moderate

- Oral steroids: dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg oral or prednisolone 1 mg/kg oral

- Consider nebulised adrenaline if persistent or worsening symptoms

- Severe

- Senior clinician review. Manage in high acuity treatment area

- Nebulised adrenaline and

- Dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg (max 12 mg) PO/IM/IV

- Life-threatening:

- Move to resuscitation area and involve senior staff

- Nebulised adrenaline 5 mL of 1:1000

- 100% oxygen 15 L/min via non-rebreather mask

- Prepare for intubation by experienced clinician (see Emergency airway management), consider croup endotracheal tubes if available

- Dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg (max 12 mg) IM/IV

- Further doses of nebulised adrenaline can be given until senior clinician available to provide airway support

Disposition

- Children can be discharged home once stridor free at rest

- A period of observation of 3 hours is required after nebulised adrenaline to ensure no recurrence of symptoms

- Consider a longer period of observation than 3 hours for a child who:

- presents overnight

- has limited access to medical care

- presents with stridor more than once during the same illness

- has risk factors for severe croup

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Severe airway obstruction present

- Child has risk factors or any doubt about diagnosis

- Child less than 6 months of age

- No improvement with nebulised adrenaline

Consider transfer when

- No improvement following nebulised adrenaline

- Child requiring repeated doses of nebulised adrenaline

- Child requiring care above the level of comfort of the local hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services

Consider discharge when

- Stridor free at rest

and - Minimum of 3 hours observation post nebulised adrenaline (if this has been required)

Parents should be advised to seek medical attention if recurrence of stridor at rest despite having received oral steroids

Parent information

Croup

Additional notes

- Antibiotics have no role in uncomplicated croup as it has a viral aetiology

- Anti-tussives such as codeine have no proven effect on the course or severity of croup, and may cause respiratory depression and increase sedation

- Cold air (below 10 °C) exposure might reduce severity in moderate croup

- Humidified air has not been proven to change the severity of croup

- Heliox has not been shown to be better than nebulised adrenaline in severe croup

Last updated September 2024