See also

Sepsis – assessment and management

Acute meningococcal disease

Child abuse

Key points

- The majority of children with petechiae do not have a serious bacterial infection or meningococcal disease, and often will not have a specific cause identified

- Seriously unwell children with petechiae/purpura require urgent management

Background

- Serious bacterial infections including meningococcal disease can present with a non-blanching rash, with or without fever

- The incidence of pneumococcal and meningococcal bacteraemia has decreased since the introduction of routine vaccination

- There are many other infective and non-infective

causes of petechiae and purpura (see table below)

Definitions

- Both petechiae and purpura do not blanch when pressure is applied - this is in contrast to other common rashes in children such as viral exanthems and urticaria

- The 'glass test' can be used to assist with assessing whether a rash is blanching - a drinking glass can be applied firmly against a rash - if the rash does not disappear it is non-blanching

Image: glass test

- Petechiae are pinpoint non-blanching spots

- Purpura are larger non-blanching spots (>2 mm)

Image: petechiae on the torso and legs of a child

Image: purpura on the torso and back/face of a child

Assessment

All children with fever and petechiae/purpura should be reviewed promptly by a senior clinician

History

- Immunisation status - children

<6 months of age or with incomplete immunisation status

- Rapid onset and/or rapid progression of symptoms and rash

- Medications: prior treatment with antibiotics may mask signs of a bacterial infection

- High risk groups: immunosuppression, previous invasive bacterial infections

- History of trauma/injury

- Association with bleeding, abdominal pain, joint pain, difficulty mobilising

- Travel

- Sick contacts

Examination

Children are considered unwell when they have:

- Abnormal vital signs: tachycardia, tachypnoea and/or desaturation in air

- Cold shock: narrow pulse pressure, cold extremities, prolonged capillary refill

- Warm shock: wide pulse pressure, bounding pulses, flushed skin with rapid capillary refill

- Altered conscious state: irritability (inconsolable crying or screaming), lethargy (including as reported by family or other staff)

- Limb tenderness or difficulty mobilising

For more information on assessment of the unwell child see

Resuscitation: Care of the seriously unwell child

For all children, also consider haematological causes and review for:

- Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

- Swelling or erythema of joints

Differential diagnoses

Causes of petechiae and/or purpura

|

Viral |

Enterovirus

Adenovirus

Influenza |

|

Bacterial |

Neisseria

meningitidis

(meningococcal disease)

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae

Group A streptococcus

Staphylococcus aureus |

|

Mechanical |

Vomiting or coughing - occurs in the distribution of the superior vena cava which is above the level of the nipples

Local physical pressure eg holding child during procedure, tight tourniquet

Non-accidental injury or accidental injury

|

|

Haematological |

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP)

Malignancy including acute leukaemia

Aplastic anaemia

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) |

|

Other |

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)

Vasculitis

Drug-induced thrombocytopenia |

Note: There are additional causes of petechiae that should be considered in newborns (eg congenital cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, neonatal lupus). Any newborn with petechiae should be promptly reviewed with a senior clinician

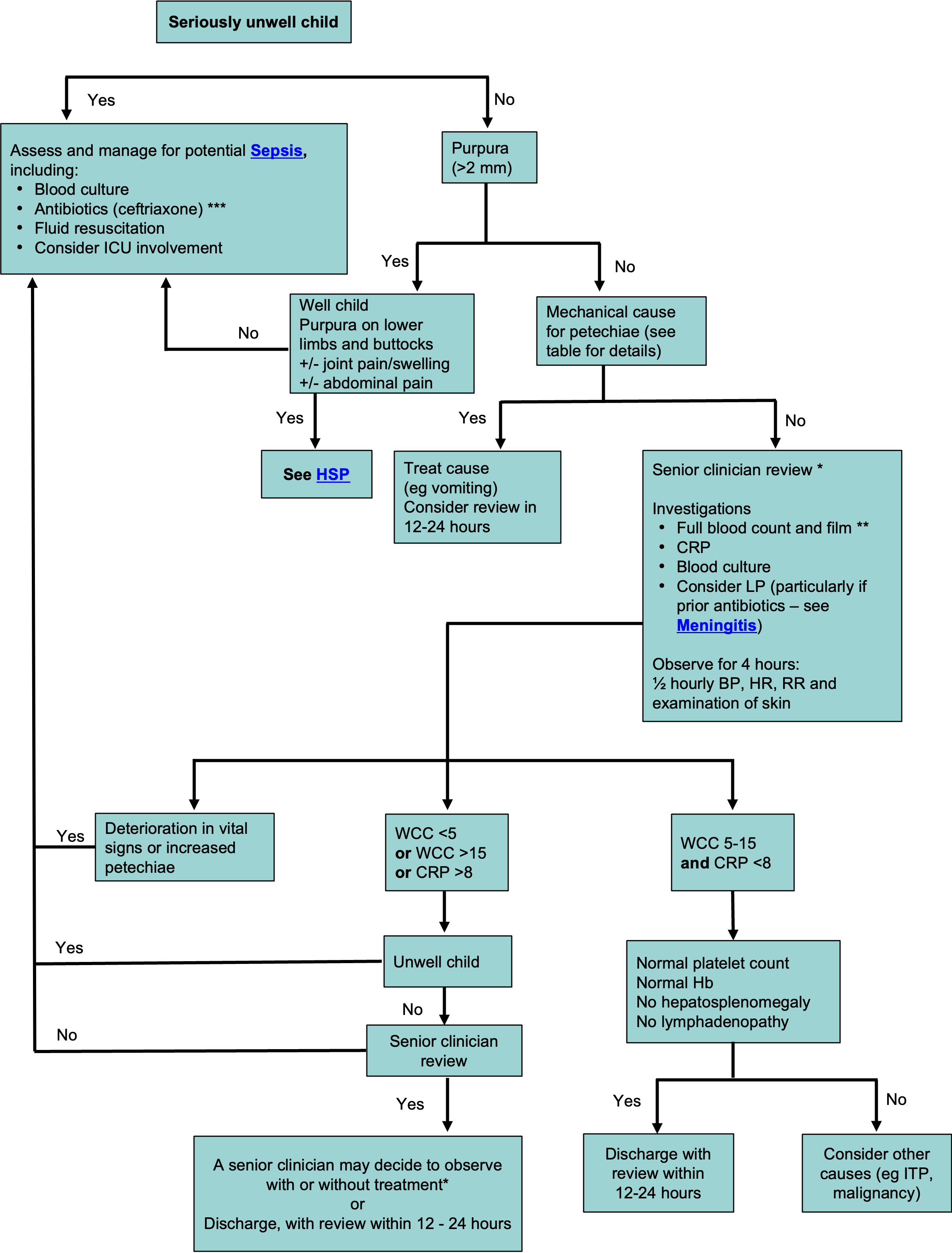

Management

Antimicrobial recommendations may vary according to local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Refer to local guidelines

* Senior clinician review may lead to decision making pathways outside of this flowchart, including the role of investigations. If a senior clinician is unavailable, the safest approach is to manage according to the flowchart.

** Film must be reviewed to exclude an alternative diagnosis

***

Antibiotics:

- Ceftriaxone:

100 mg/kg (4 g) IV daily (where possible, ceftriaxone should be avoided in neonates <41 weeks gestation, particularly if jaundiced or receiving calcium containing solutions, including TPN)

- Cefotaxime: 50 mg/kg (2 g) IV 12H (week 1 of life), 6-8H (week 2-4 of life), 6H (>week 4 of life)

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Assessing any unwell child, including any with suspected meningococcal disease

- Uncertainty about diagnosis or to arrange follow-up

- Advice regarding escalation of care

Consider transfer when

Child requiring care beyond the comfort level of the hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see

Retrieval Services.

Consider discharge when

- Serious cause of petechiae/purpura considered unlikely based on clinical assessment and/or investigations

- Always advise parents to return for review if their child becomes more unwell or there is concern

Parent information

Rashes

Fever in children

Last updated February 2021