See also

Fever and petechiae

The acutely swollen joint

Hypertension

Haematuria

Key points

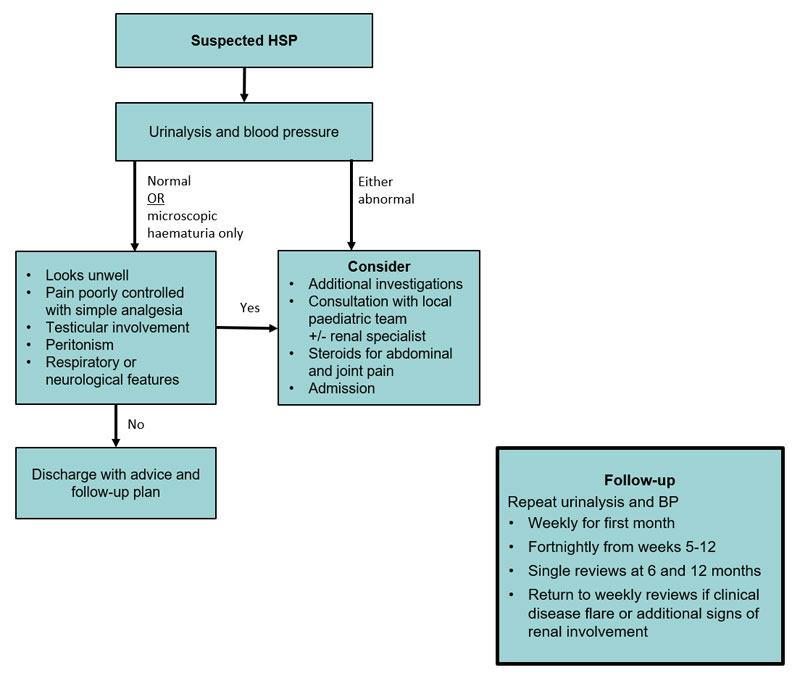

- Urinalysis and blood pressure measurement must be done when Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is suspected

- Most cases are self-limiting and only require symptomatic management

- Close follow-up is critical to identify significant renal involvement requiring intervention. Renal involvement is usually asymptomatic

Background

HSP is the most common vasculitis of childhood. It most commonly affects children 2-8 years of age

Assessment

HSP is a clinical diagnosis

The features include rash, and one or more of:

- Arthritis/arthralgia (50-75%)

- Abdominal pain (50%)

- Nephritis (25-50%)

History

- The clinical manifestations of HSP can take days to weeks to fully develop and may vary in order of appearance

- Purpura occurs in all patients but is the presenting complaint in only 75% of cases

- Recent upper respiratory tract infection is present in 50% of HSP cases, commonly viral or Group A streptococcus infections

Examination

|

Assess for |

Features |

General observations |

Hypertension |

Blood pressure must be measured at initial presentation and at follow-up |

Skin |

Palpable purpura, petechiae and ecchymoses

May be preceded by urticarial, erythematous, maculopapular or bullous skin lesions |

Usually symmetrical

Located on gravity/pressure-dependent areas (eg buttocks & lower limbs in ambulatory children) |

Painful non-pitting subcutaneous oedema |

Commonly periorbital (in non-ambulant child), and/or dependent areas (hands, feet, scrotum) |

Joints |

Arthralgia +/- arthritis |

Usually affects large joints of lower limbs. Rarely upper limbs.

Usually no significant effusion or warmth |

Abdominal |

Diffuse abdominal pain Generalised tenderness

Signs of bowel obstruction

Peritonism |

Most common complication is intussusception

Others include GI haemorrhage, bowel ischaemia, necrosis or perforation, protein-losing enteropathy, pancreatitis |

Genital |

Testicular pain +/-

orchitis +/- necrosis

Cord haematoma |

Exclude testicular torsion |

Respiratory (rare) |

Respiratory distress |

Diffuse alveolar haemorrhage |

Neurological (rare) |

Changes in mental status |

Labile mood, apathy, hyperactivity, encephalopathy |

Focal neurological signs |

Consider intracranial haemorrhage |

Urinalysis |

Haematuria (microscopic or macroscopic)

Proteinuria (mild to severe) |

Proteinuria/haematuria, nephrotic syndrome, acute nephritic syndrome, hypertension, renal impairment, renal failure |

Typical rash distribution

Management

Investigations

Urinalysis is usually the only investigation needed in a classic presentation of HSP

If there is hypertension, macroscopic haematuria or significant proteinuria, also perform:

- Formal urine microscopy and urinary protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR)

- UEC and albumin

Additional investigations may be required to rule out differentials if the diagnosis is unclear (eg ITP, leukaemia, meningococcal infection) or to identify potential complications of HSP:

- FBE, UEC, albumin

- Blood and urine cultures

- Abdominal imaging

- ASOT and anti-DNAse B

- ANA, dsDNA, ANCA, C3, C4 if significant renal involvement with an unclear diagnosis

Treatment

Mild pain

- Subcutaneous oedema is managed with bed rest and elevation of the affected area

- Regular paracetamol and a short course of NSAIDs such as ibuprofen 10 mg/kg (max 400 mg) TDS or naproxen 10 mg/kg (max 500 mg) BD can be used if not contraindicated (eg GI bleeding or renal impairment)

Moderate-severe pain

- Consider the use of steroids (glucocorticoids) in children with moderate to severe abdominal and joint pain (may reduce duration of symptoms)

- Steroids do not impact the rate of long-term renal complications of HSP

- If prescribing oral prednisolone, give 1-2 mg/kg/day (maximum 60 mg/day) or IV methylprednisolone 0.8-1.6 mg/kg/day (maximum 1 g/day) while symptoms persist. Once symptoms have resolved, an appropriate weaning regimen should be used

Follow-up

- Regular GP or paediatrician review is critical to identify subsequent renal involvement which rarely requires a renal biopsy +/- immunosuppression

- If initial urinalysis is normal or only reveals microscopic haematuria, review clinically and check BP/urinalysis:

- Weekly for the first month after disease onset

- Fortnightly from weeks 5-12

- Single reviews at 6 and 12 months

- Return to weekly reviews if there is a clinical disease flare or additional signs of renal involvement

- If there is no significant renal involvement and normal urinalysis at 12 months, no further follow-up is required

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

Consider admission

- Serious abdominal complications

- Severe debilitating pain

- Severe renal involvement (see UPCR values below)

- Neurological or pulmonary involvement

- If treatment with prednisolone is considered

The development of hypertension, proteinuria or macroscopic haematuria at any point should prompt a paediatric review and the investigations as outlined above

Consider consultation with a renal specialist when

- Hypertension

- Abnormal renal function

- Macroscopic haematuria for 5 days

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Acute nephritic syndrome

- Persistent proteinuria

- UPCR >250 mg/mmol for 4 weeks

- UPCR >100 mg/mmol for 3 months

- UPCR >50 mg/mmol for 6 months

Consider transfer when

The care required for the child is beyond the comfort level of the health care service

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval services

Consider discharge when

Appropriate follow up has been arranged

Discharge advice

Prognosis

- A first episode of HSP, in the absence of significant renal disease, usually resolves within 4 weeks. Rash is often the last symptom to remit

- Joint pain usually resolves spontaneously within 72 hours

- Uncomplicated abdominal pain usually resolves spontaneously within 24-48 hours

- In 25-35% of patients, HSP recurs at least once, within 4 months of the initial presentation. Subsequent episodes are usually associated with milder symptoms that are shorter in duration than previous episodes

- 90% of those who develop renal complications do so within 2 months of the onset, and 97% within 6 months

Parent information sheet

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Pain relief for children

Urine samples

Starship HSP Record

Last Updated January 2021