See also

Abdominal pain – acute

Acute pain management

Key points

- The diagnosis of intussusception requires a high index of suspicion. Consider intussusception in infants and children with intermittent distress, vomiting or isolated unexplained lethargy

- Delayed presentation of intussusception can manifest as small bowel obstruction, bowel perforation, peritonitis and/or shock

- Ultrasound is the initial study of choice

Background

Intussusception is the invagination (telescoping) of a proximal segment of bowel into the distal bowel lumen. The commonest site is a segment of ileum moving into the colon through the ileo-caecal valve. This process leads to bowel obstruction, venous

congestion and bowel wall ischaemia. Perforation can occur and lead to peritonitis and shock

- The triad of intermittent abdominal pain, palpable abdominal mass and red currant jelly stools occurs in only 1/3 of children

- May occur at any age, but most commonly between 2 months and 2 years of age

- Most cases are idiopathic (90%)

- In older children, a pathological lead point may be the cause

Assessment

History

- Intermittent

pain or distress

- Episodes can recur within minutes to hours and may increase in frequency over the next 12–24 hours

- The child may appear very well between episodes

- Pallor, especially during episodes

- Lethargy may be the only presenting symptom. It may be profound, episodic or persistent

- Vomiting is usually a prominent feature (but bile stained

vomiting is a late sign and indicates a bowel obstruction)

- Diarrhoea is quite common initially and can lead to a misdiagnosis of gastroenteritis. Rectal

bleeding or the classic “red currant

jelly” stool are late signs suggesting bowel ischemia and infarction

Additional risk factors

- Recent intussusception (may present with more subtle symptoms)

- Potential lead point – eg Meckel’s diverticulum, Henoch Schonlein Purpura, lymphoma, luminal polyps (eg Peutz Jegher Syndrome)

- Recent bowel surgery

- Recent rotavirus vaccination

Examination

- Abdominal mass may be felt – typically a sausage shaped mass in the right abdomen, crossing the midline in the epigastrium or behind umbilicus (in 2/3 of children). The abdominal mass may be subtle and examination is best performed when the child is

settled in between episodes

- Abdominal distension suggests bowel obstruction

- Tenderness or guarding may suggest perforation and peritonitis

- Inspection of the nappy and perianal region should be done. A rectal examination is rarely indicated

- Infants may present with Hypovolaemic shock

Management

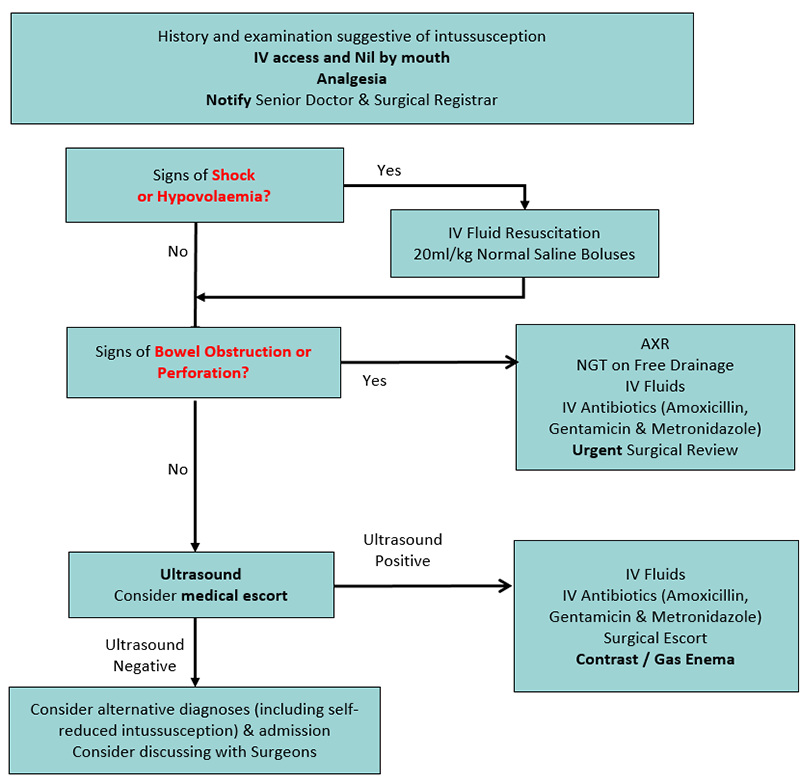

- Analgesia and resuscitation should precede investigation (see flowchart below)

- Secure IV access for all children suspected to have intussusception before diagnostic imaging

- Treat hypovolaemic shock with IV boluses of 20 mL/kg normal saline

- Give adequate analgesia (usually intranasal fentanyl or IV morphine). See Acute pain management

- Involve the surgical team early

- Keep nil orally

- Pass nasogastric tube if bowel obstruction or perforation on AXR, or if planning transfer by air

- Children with intussusception can decompensate while undergoing ultrasound and/or air enema. Ensure medical or nursing escorts are capable of providing resuscitation if needed

Investigations

Ultrasound scan

- High sensitivity (>98%) and specificity (>98%) when performed by an experienced paediatric ultrasonographer

- Point of Care Ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis of intussusception by appropriately trained clinicians. It should not be used to exclude the diagnosis

Abdominal

X-Ray

- Perform AXR only if there are signs of obstruction or perforation

- A normal AXR does not exclude intussusception (sensitivity

<50%)

- Signs suggesting intussusception on an abdominal x-ray include:

- an abnormal gas pattern, with an empty right lower quadrant and visible soft tissue mass in the upper abdomen

- a soft tissue mass surrounded by a crescent lucency of bowel gas (crescent sign)

- lack of faecal material in the large bowel

- signs of small bowel

obstruction

- pneumoperitoneum indicating bowel perforation

Contrast / gas enema

- The enema may be used diagnostically and therapeutically in consultation with a surgical team

- There is a small risk of bowel perforation and bacteraemia during the gas enema. Therefore, the enema is performed where paediatric surgery is available in case of the need for laparotomy. Usually, a surgical doctor, as well as a suitably trained nurse, will

accompany the child with appropriate resuscitation equipment

- Contraindicated if peritonitis, shock, perforation, or an unstable clinical condition is present

Blood tests

- Blood glucose

- Venous Gas, FBE and UEC if the child looks unwell

- Blood group and hold prior to theatre

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

There is suspicion of intussusception – (all suspected cases)

Consider transfer when

Child requiring care beyond the capability of the hospital

Note: when transferring infants or children with possible surgical conditions, ensure they have adequate analgesia, venous access and intravenous fluids prior to transfer, as third space losses can be large and lead to haemodynamic collapse. Consider a nasogastric tube on free drainage if

transferring by air.

For emergency advice

and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval Services

Parent information

Abdominal pain

Reducing your child’s pain during investigations and procedures

Pain relief for children

Intussusception

Last Updated August 2019