See also

Acute meningococcal disease

Afebrile seizures

CSF interpretation

Febrile child

Lumbar puncture

Key points

- Making a clinical distinction between meningitis and encephalitis can be difficult, but is important, as the common causative pathogens differ. If there is any doubt, initial empiric management should cover both

- If meningitis or encephalitis is clinically suspected and lumbar puncture is contraindicated or will be delayed more than 30 minutes, give empiric intravenous antimicrobials and consider steroids

- Consider herpes simplex virus (HSV) encephalitis in any child with encephalopathy, and in neonates. Treat with aciclovir

Background

- Meningitis is inflammation of the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord

- Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain parenchyma

- Bacterial meningitis is a medical emergency which requires empiric antibiotic treatment without delay. A high index of suspicion for meningitis is needed in any unwell child, particularly if there is altered mental state or no clear focus of infection

- Presentation of bacterial meningitis can vary from fulminant (hours) to insidious (days) and can be altered by recent treatment with antibiotics

- It is difficult to distinguish viral from bacterial meningitis clinically. Children with meningitis should be treated with empiric antimicrobials until the cause is confirmed

- Unrecognised HSV encephalitis is a devastating illness with significant morbidity and mortality, however early treatment with aciclovir can lead to a full recovery

- Vaccines have significantly reduced the incidence of bacterial meningitis eg Haemophilus influenzae type B (HiB) vaccine, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, meningococcal ACWY and B vaccines

Assessment

Making a clinical distinction between meningitis and encephalitis can be difficult, but is important, as the common causative pathogens differ. If there is any doubt, initial empiric management should cover both

|

Meningitis |

Encephalitis |

History |

Fever

Infant:

- subtle or non-specific symptoms

- irritability

- lethargy or drowsiness

- poor feeding

- apnoea

- vomiting and diarrhoea

- temperature instability

Child (any of the above and/or):

- headache

- neck pain

- photophobia

- nausea

- altered conscious state

Preceding URTI may be present

Seizures

Recent antibiotics

Immunisation history

Travel history

Medical condition that may predispose child to meningitis eg CNS anatomical abnormality or shunt, immunosuppression, immunodeficiency |

Fever

Features of altered mental state can be subtle and depend on the affected region of the brain:

- unusual behaviour

- confusion

- personality change

- emotional lability

Seizures (common)

Abnormal movements

Headache

Vomiting

Lethargy

Features of prodromal illness

Exposure history:

- travel

- location eg NT, far north Australia

- mosquito, tick or insect bites

- animal contact

Maternal HSV

Immunisation history

Immunosuppression or immunodeficiency

Consider other causes of encephalopathy eg acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), toxins or metabolic |

Examination |

Full or bulging fontanelle

High-pitched cry

Fever or hypothermia

Hyper or hypotonia

Neck stiffness (may be absent in infants)

Focal neurological signs

Purpuric rash (see Petechiae and purpura)

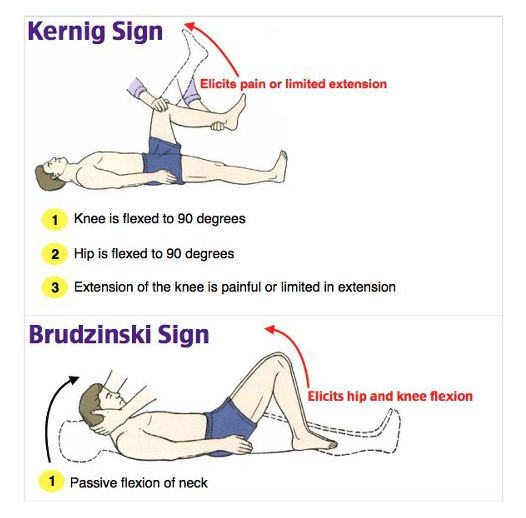

Pain and involuntary effort to reduce meningeal “stretch” eg Kernig and Brudzinski signs (see Additional notes below) |

Altered conscious state

Confusion

Fever

Bradycardia and hypertension can be signs of raised intracranial pressure

Focal neurological signs

Abnormal movements eg chorea

Vesicular rash, corneal ulcer/keratitis (HSV) |

Risk factors for meningitis

- Maternal group B streptococcal (GBS) colonisation in infants <3 months

- Unimmunised

- Immunocompromised (consider cryptococcus and mycobacteria)

- History of neurosurgery or penetrating head injury

- VP shunt

- Cochlear implant

- Younger age, particularly <5 years

Management

Investigations

Urgent lumbar puncture (LP)

- Urgent CSF microscopy and biochemistry, preferably with simultaneous blood glucose

- Based on clinical presentation and initial CSF results, consider further investigations such as multiplex PCR (eg BioFire®) or specific PCR testing for enterovirus, parechovirus, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae or HSV

- If unsafe to perform (eg focal neurological signs, ongoing seizures, markedly reduced GCS, cardiovascular compromise or coagulopathy), defer LP and commence empiric treatment immediately. The LP should be performed as soon as practicable, once deemed safe by a senior clinician. Tachycardia and tachypnoea without respiratory compromise are not contraindications to lumbar puncture

- Do not delay antimicrobials in an unwell child if the LP will take more than 30 minutes

Blood

- Blood culture

- FBE (may be normal)

- Blood glucose level

- Blood gas for lactate

- UEC, assess for hyponatraemia

- Consider coagulation studies if shock or coagulopathy suspected

- Consider LFTs, metabolic and toxicology testing if non-infective cause of encephalopathy is suspected

- Consider serum bacterial and viral PCR

Neuroimaging

- Indications include:

- focal neurological signs

- signs of raised ICP

- encephalopathy

- diagnostic uncertainty eg to look for a mass

- Not routine in meningitis but may be used to look for complications eg abscess, thrombosis

- Normal CT brain does not exclude raised ICP and should not influence the decision to perform an LP

- MRI will provide more detailed information to guide diagnosis, but may require general anaesthetic

- EEG may be helpful in suspected encephalitis

Treatment

- Initial empiric management should cover meningitis. Treatment for encephalitis should be added if there is clinical suspicion (altered conscious state, focal neurological signs, seizures, signs or risk of HSV infection) and/or child is obtunded

- Antibiotics should be given within 30 minutes of the decision to treat

- Consider giving steroid with the first dose of antibiotics

- Antimicrobial recommendations may vary according to local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Refer to local guidelines

Suggested antibiotic regimen

(if local guidelines not available)

| Age group |

Common organisms |

Empiric antibiotic |

Dexamethasone |

Meningitis |

0-2 months |

GBS, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes (rare) |

Benzylpenicillin 60 mg/kg

IV 12 hourly (<7 days old),

6-8 hourly (7 days to <4 weeks old), 4 hourly (>4 weeks old)

and

Cefotaxime 50 mg/kg

IV 12 hourly (week 1 of life),

6-8 hourly (7 days to <4 weeks old),

6 hourly (>4 weeks old) or Ceftriaxone 100 mg/kg (max 2 g) IV daily*

|

Not advised |

≥2 months |

N meningitidis,

S pneumoniae, HiB |

Ceftriaxone 100 mg/kg (max 4 g) IV daily or cefotaxime 50 mg/kg (max 2 g) IV 6 hourly

Add vancomycin if Gram-positive cocci on Gram stain (see Vancomycin for dosing) |

0.15 mg/kg (max 10 mg) IV 6 hourly for 4 days |

Penicillin/cephalosporin hypersensitivity: moxifloxacin 10 mg/kg (max 400 mg) IV daily and vancomycin (see Vancomycin for dosing) |

Encephalitis

Antibiotics as above, plus: |

|

HSV

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

EBV, CMV, HHV6, Influenza

Arboviruses |

Aciclovir 20 mg/kg IV 12 hourly (<30 weeks gestation), 8 hourly (>30 weeks gestation to <3 months corrected age)

500 mg/m2 or 20 mg/kg IV 8 hourly (3 months to 12 years)

10 mg/kg IV 8 hourly (>12 years)

Consider adding azithromycin |

Not advised |

* Where possible, ceftriaxone should be avoided in neonates <41 weeks gestation, particularly if jaundiced or receiving calcium containing solutions, including TPN

Steroids

- Current evidence for steroids in bacterial meningitis in children is mixed, but suggests that steroids may reduce the risk of hearing loss

- Steroids are not recommended in neonates due to possible effects on neurodevelopment

- Give the first dose of IV dexamethasone just before or with the first dose of antibiotics. If giving the first dose of IV dexamethasone after initial antibiotic administration, this should ideally be done within 4 hours and not more than 12 hours after starting antibiotics

Ongoing management

- All seizures in the setting of meningitis or encephalitis should be treated immediately

- Fluid management: see IV fluids

- Initial resuscitation, if required to manage shock, should be with 10 mL/kg 0.9% sodium chloride IV boluses

- Children with CNS infections are at higher risk of excess antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion and caution should be taken with ongoing fluid management. A maximum of 2/3 maintenance IV fluids should be administered as per IV fluids

- Further fluid restriction may be required if there is hyponatraemia or risk of raised intracranial pressure, seek senior advice

- In all children with meningitis, regardless of the presence of intracranial hypertension it is essential to ensure normal blood pressure and adequate circulating volume

- Assessment of the clinical signs of hydration, including weight, measurement of the serum sodium and acid-base status, and clinical assessment of the neurological state should be repeated every 6-12 hours for the first 48 hours

- Monitor

- weight

- head circumference under 2 years

- vital signs including HR and BP

- electrolytes, urea, creatinine and blood glucose

- Isolation: droplet precautions in first 24 hours of admission

- Chemoprophylaxis for contacts

Directed treatment

Antimicrobial recommendations may vary according to local antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Refer to local guidelines

Suggested antibiotic regimen

(if local guidelines not available)

| Organism |

Antibiotics |

Duration (days) |

N meningitidis |

Benzylpenicillin |

7 |

S pneumoniae (penicillin sensitive) |

Benzylpenicillin |

10 |

S pneumoniae (penicillin resistant) |

Cefotaxime/ceftriaxone, Vancomycin if cephalosporin resistant |

10 |

Haemophilus influenza B (HiB) |

Ceftriaxone/cefotaxime |

10 |

Gram-negative |

Ceftriaxone/cefotaxime |

21 |

Organism not isolated |

Ceftriaxone/cefotaxime |

7 minimum |

GBS, Listeria |

Benzylpenicillin |

14-21 |

HSV |

Aciclovir |

21 minimum |

Consider infectious diseases consultation for those with organisms resistant to first line therapy or with immediate hypersensitivity to penicillins/cephalosporins

Notification

- All cases of presumed or confirmed N meningitidis and HiB should be notified to the Health Department immediately

- Confirmed S pneumoniae is notifiable within 5 days

- Follow state guidelines

Complications

- Multi-organ involvement due to primary pathogen or secondary to septic shock eg hepatic or cardiac

- Venous sinus thrombosis

- Hydrocephalus

- Seizures, subsequent epilepsy

- If fever persists after 4-6 days of treatment, consider:

- nosocomial infection

- subdural effusion or empyema

- cerebral abscess or parameningeal focus

- inadequate treatment

- Hearing impairment

- Neurodevelopmental impairment

- Permanent focal neurological deficit

Hearing loss

- S pneumoniae meningitis has the highest risk of hearing loss (approximately 22% of cases)

- Onset can occur as early as 48 hours

- High risk of cochlear ossification, which can inhibit future surgery. Early identification of hearing loss, and intervention, may improve outcome

- Audiology testing ideally should be done while still an inpatient (as a baseline)

- Key management should include

- Close follow up with paediatric team, monitoring hearing and development

- Education of parents to flag concerning features for hearing loss

- Early referral to audiology and ENT for prompt and close follow up

Follow-up

- All children with encephalitis or bacterial meningitis should have formal audiology assessment 6-8 weeks after discharge (earlier if concerns)

- Neurodevelopmental progress should be monitored

- Consider investigating for complement deficiency if the child has had >1 episode of meningococcal disease

Consider consultation with local paediatric team

- All children with suspected encephalitis or bacterial meningitis

- All children with concern for non-infectious encephalopathy

Consider transfer when

- Haemodynamic or respiratory instability

- Altered conscious state, seizures or focal neurological signs

- Child requiring care above the level of comfort of the local hospital

- Complications of meningitis or encephalitis or poor response to treatment

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see Retrieval services

Consider discharge when

Children can complete IV treatment through HITH services if available once haemodynamically stable, afebrile and decision made regarding directed treatment

Parent information sheet

Lumbar puncture

Meningitis

Meningococcal infection

Additional notes

Kernig sign

- Child is supine

- One hip and knee are flexed to 90 degrees by the examiner

- The examiner then attempts to passively extend child’s knee

- Positive if there is pain along spinal cord, and/or resistance to knee extension

Brudzinski sign

- Child is supine with legs extended

- The examiner grasps child’s occiput and attempts neck flexion

- Positive if there is reflex flexion of child’s hips and knees with neck flexion

Last updated October 2024