See also

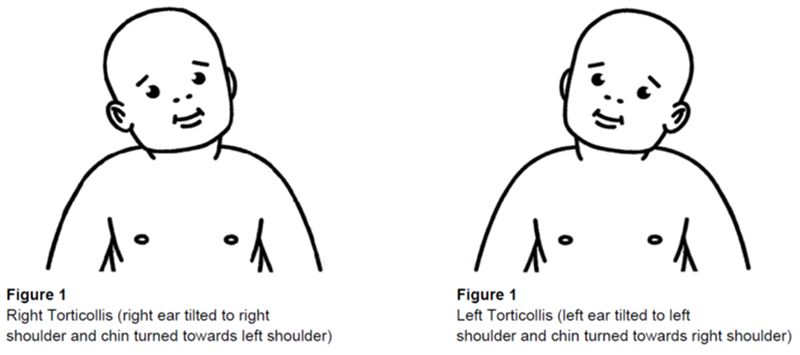

Congenital torticollis

Key Points

- Common, benign condition that affects the cosmetic appearance of an infant’s head. Does not cause developmental delay

- Imaging is not required, diagnosis is based on history and examination findings including the absence of features of craniosynostosis

- Assessment includes identifying the presence of a co-existing tight sternocleidomastoid muscle (congenital muscular torticollis) and other risk factors

- Most resolve without any treatment and will show improvement with counterpositioning measures and physiotherapy intervention

Background

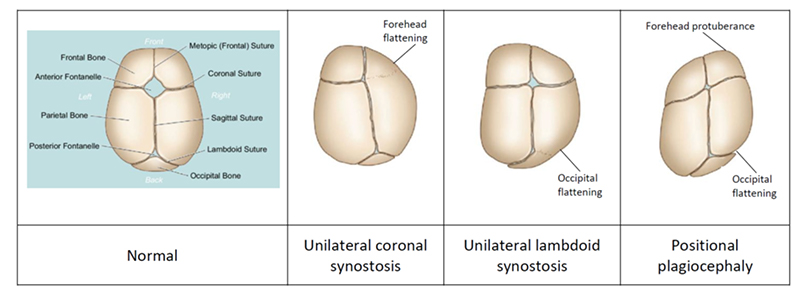

Types of head shape deformities

Positional plagiocephaly

- Skull deformation involving posterior flattening of either side of the head. This may result in ear misalignment and facial asymmetry

Other positional head shape deformities

- Brachycephaly: symmetrical occipital flattening and widening of the head, which often co-exists with positional plagiocephaly

- Scaphocephaly: elongated narrow skull with flattening on both sides of the head, occipital bulge and frontal bossing

Causes and natural history

- External moulding forces due to the infant lying on their back or unilateral posture preference

- Risk factors

- low tone

- delayed gross motor development

- minimal tummy time

- tight sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle (congenital muscular torticollis)

- developmental dysplasia of the hip

- Over one third of infants have plagiocephaly in the first few months of life which improves once the infant can move their head independently

- Most resolve without intervention (self-correction) by the time the infant can sit without support

- Self-correction occurs because of the rapid cranial growth in the first 4-6 months of life (for premature infants use 4-6 months corrected age), and ongoing growth until the anterior fontanelle closes

- Self-correction in brachycephaly is evident when there is an occipital ridge present (bone remodelling starts at the base of the occiput and moves upwards towards the crown)

- Plagiocephaly and brachycephaly are present in around 1% of teenagers

Differential diagnosis

- Craniosynostosis

- Craniofacial anomaly causing skull deformity which may be associated with abnormal brain development

- Caused by premature fusion of one or more skull sutures resulting in ridging of sutures

- Does not improve over time

- May be an isolated finding with a single suture involved, or may be associated with other syndromes eg Apert, Crouzon syndrome

- Craniosynostosis with similar head shape to plagiocephaly

- Unilateral coronal craniosynostosis (causes forehead flattening)

- Unilateral lambdoid craniosynostosis (causes occipital flattening on the opposite side to the forehead protuberance)

Conditions associated with positional plagiocephaly

Congenital muscular torticollis

- Tightening/contracture of the SCM muscle due to limited intrauterine space (multiple pregnancy, oligohydramnios)

- Usually noted within the first month of life

- Clinical features

- head tilt toward the same side as the tight SCM muscle

- tendency to look to the opposite side of the tight SCM muscle

- plagiocephaly on the opposite side of the tight SCM muscle

- lump in the SCM muscle may be palpable

- Early identification and management including referral to physiotherapist is beneficial as plagiocephaly will improve once the tight SCM is treated

Visual impairment

- reduced vision and nystagmus result in head tilt to improve visual clarity

Cervical scoliosis

Assessment

Assess an infant for positional plagiocephaly if they present with one or more of the following

- Head turning preference to one side

- Head tilt

- Posterior flattening on one side of the head (though parents may report a bump/bulge on the opposite ‘normal’ side)

- Symmetrical occipital flattening (brachycephaly)

- Ear displacement

- Asymmetrical protuberance of the forehead

- Facial asymmetry (one eye appears smaller)

History

- Birth history (breech, multiple birth) and gestational age

- Preference for looking to one side only during awake and asleep time

- Assess for risk factors

- Gross motor development eg head control, tone, sitting supported, tolerance of tummy time

- Parent/carer preference in infant handling and positioning eg front or back sleeping, preferred feeding or carrying position

- Onset and change in head shape over time (worsening or improvement)

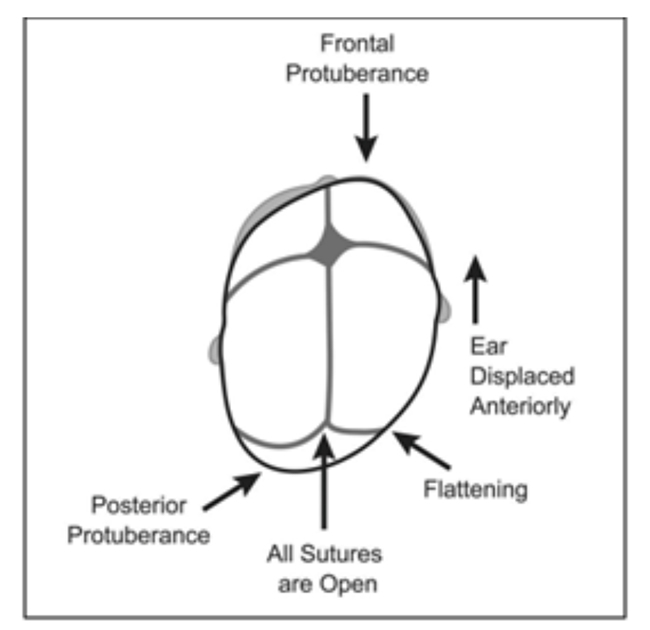

Examination

- Determine the type and severity of the head shape deformity

- Assess for co-existing tight SCM (and other associated conditions)

- Exclude craniosynostosis

- Place infant on parent’s lap with examiner standing at the infant’s back

- Observe head from above. Features which support a clinical diagnosis of plagiocephaly:

- parallelogram shape head

- frontal protuberance on same side as posterior flattening

- ear pushed forward on same side as posterior flattening

- posterior protuberance (‘bump’) on the opposite ‘normal’ side

- Turn infant so their back is to parent’s chest

- Observe infant’s head front on:

- The eye on the affected side may look bigger or the cheek can be pushed forward in infants with plagiocephaly

- Assess for features of a tight SCM muscle eg head tilt, restricted range of cervical rotation

- Palpate

- Size of anterior fontanelle

- The anterior fontanelle can vary in size from small to large

- 1% have a closed fontanelle at 3 months of age, 38% at 12 months of age, 96% at 24 months of age

- The size of the anterior fontanelle is useful in predicting response to physiotherapy or helmet therapy. An infant with an open fontanelle has more capacity for cranial growth and re-modelling

- Features of craniosynostosis: ridging of coronal or sagittal sutures

- Other: head circumference, eye movements, back and spine, and neurological examination to exclude other conditions associated with plagiocephaly

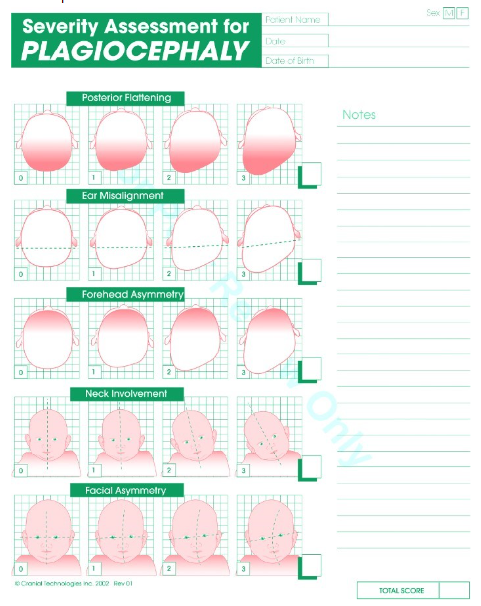

Severity

Severity assessment can be used to guide the need for referral to a specialist service and help monitor progress

Different modalities are available to assess the severity of the head shape deformity. One example of these is the ‘Severity assessment for plagiocephaly, brachycephaly or scaphocephaly’ scale (see Additional notes). Severity assessment is best undertaken by a clinician familiar with the severity scale, including community paediatric physiotherapists, who can provide ongoing follow-up

Management

Investigations

- Imaging (eg cranial X-ray or CT scan) not required to confirm plagiocephaly or brachycephaly

- If craniosynostosis is suspected, refer urgently to a craniofacial service that can decide on optimal diagnostic imaging. This reduces delay in appropriate management

Treatment

Do not use any pillow during sleep to prevent or manage flattening due to the risk of sudden infant death syndrome

Counterpositioning

- Reducing the amount of time the infant spends lying on the flat side of their head will help improve the head shape. This is achieved by counterpositioning measures

- Counterpositioning promotes active positioning of the head towards the opposite side of the flattening, by organising the environment so the infant is encouraged to turn towards that side

Counterpositioning examples for an infant with right sided plagiocephaly:

- Sleep time

- While in their cot, the infant will tend to look towards the doorway or centre of the room. Change the position of the cot so the infant looks to the left when the parent/caregiver enters the room

- Awake time

- Lay the infant on their left shoulder/side and place toys in front

- Lay the infant on their back and place toys on their left side

- Regular

tummy time strengthens the muscles of the neck and helps develop head control

- Carry the infant in a position which encourages head turning to the left

Physiotherapy

- A physiotherapist can provide parent education, recommendations for infant handling, counterpositioning as well as specific exercises if

congenital torticollis is present. Exercises for congenital muscular torticollis include passive stretching and strengthening of the opposite SCM muscle

- A physiotherapist can monitor for improvement in head shape and provide guidance as to whether specialist referral is required

Use of helmets

- There is some evidence for benefit of the use of a helmet in infants with severe deformity that is not improving with counterpositioning and physiotherapy

- Even with helmet therapy there will be residual deformity of the skull

- Optimal timing is around 6-7 months of age. Children with developmental delay or torticollis can be considered for a helmet with less deformity as these children are less likely to self-correct over time (because they spend more time on the flat spot)

- Unlikely to benefit infants >10 months of age due to the slowing of skull growth and anterior fontanelle closure

- Helmet therapy for plagiocephaly removes the pressure over the flat area, allowing the skull to grow into the space provided. For brachycephaly, it improves occipital growth and prevents further widening (it does not reverse it)

- Custom made and fitted by an orthotist. Worn 23 hours per day for an average duration of 6 weeks to 3 months, depending on the improvement in head shape

- Assessment for suitability is available in public clinics or private orthotist services

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

Refer to specialist clinic (paediatrics or craniofacial service) when

- Infant with severe positional head shape, worsening with time and not responding to general measures eg counterpositioning, physiotherapy

- Infant with suspected craniosynostosis

- Infant with congenital muscular torticollis not improving with community physiotherapist

Parent information

Plagiocephaly – misshapen head

Babys head shape fact sheet

TummyTime (rednose.org.au)

Additional notes

Example severity assessment scale for positional plagiocephaly

- Includes a score from 0 (no asymmetry) to 3 (severe asymmetry) in each of the clinical features (posterior flattening, forehead asymmetry, ear misalignment, heat tilt and facial asymmetry) of plagiocephaly

- Scoring thresholds for consideration of helmet therapy may vary, seek local specialist advice

Last updated January 2024