|

Head and face

|

- Face, scalp and skull

- Bleeding, lacerations, bruising, swelling, depressions/irregularities in the skull (to suggest skull fracture), bruising behind the ears (Battle’s sign: may indicate base of skull fracture), periorbital bruising (“Racoon eyes”: may indicate base of skull fracture)

- Eyes

- Palpate bony margins of orbit for fracture. Test eye movements, pupillary reflexes and vision. Inspect for penetrating injury (see Penetrating eye injury), irregular iris, foreign bodies, subconjunctival haemorrhage, hyphema

- Ears

- Bleeding, blood behind tympanic membrane (suggestive of base of skull fracture), tympanic membrane perforation (in blast injuries). Assess hearing

- Nose

- Bleeding, septal haematoma, CSF leak, palpate for bony crepitus or deformity

- Mouth

- Wounds to the lips, gums, tongue or palate

- Teeth

- Jaw

- Identify pain, trismus or malocclusion and palpate for bony step

|

|

Neck

|

Inspect neck, whilst maintaining manual in-line stabilisation if C-spine has yet to be cleared. Open collar to do this

Examine anterior neck for blunt or penetrating trauma by looking/feeling for the following (TWELVE-C):

- Tracheal deviation

- Wounds

- Emphysema (subcutaneous)

- Laryngeal tenderness/crepitus

- Venous distension

- OEsophageal injury (unlikely if child can swallow easily)

- Carotid haematoma/bruits/swelling

Assess C-spine if not completed in secondary survey. See C-spine assessment

|

|

Chest

|

- Observe work of breathing and effectiveness of breathing

- Assess for any asymmetrical or paradoxical chest wall movement

- Inspect for signs of injury such as bruising, seatbelt marks, wounds

- In cases of stabbing or other assault, look for ‘hidden’ wounds by checking areas such as axillae

- Palpate for bony tenderness over ribs, crepitus (indicating subcutaneous emphysema)

|

|

Abdomen

|

- Inspect for bruising (eg from seatbelt or handlebar injury), abdominal distension

- Palpate for signs of peritonism such as guarding or rigidity

- Palpate for tenderness over the liver, spleen, kidneys and bladder

|

|

Pelvis and perineum

|

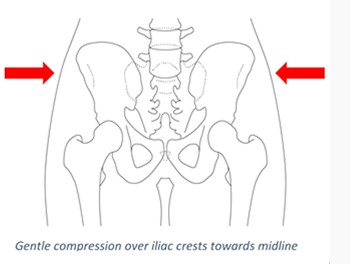

- Inspect for grazes over iliac crests, bruising, deformity

- Feel for pain or crepitus on gentle palpation of bony prominences

- Assess for pelvic instability by gentle compression of the iliac crests

- Stressing/springing the pelvis is not recommended

- Genital, if pelvic injury or high chance of injury needs external examination. Should include perineum

|

|

Limbs

|

Most common missed injuries, especially hands

- Inspect for wounds, bruising, open fractures, burns, abrasions

- Feel for soft tissue and bony tenderness or swelling, joint movement and stability

- Examine pulses and perfusion

- Examine sensory and motor function of any nerve roots or peripheral nerves that may have been injured

- Assess gait if possible

|

|

Back and spine

|

- A log roll should be performed if spinal precautions required

- Inspect entire length of back and buttocks

- Palpate then percuss spine for tenderness

- Palpate scapulae and sacroiliac joints for tenderness

|