See also

Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute management

Autism and developmental disability: management of distress/agitation

Key points

- The procedure should emphasise safety and non-restraint strategies in the first instance

- The Code Response team should perform this procedure

- Any physical restraint is a last resort, and should only be used to facilitate rapidly effective pharmacological treatment

- The terms Code Grey and Code Black are used interchangeably across states; here we refer to Code Response as a universal approach

Background

Principles

- Physical restraint should only be used to facilitate rapidly effective pharmacological treatment

- A key principle of medical ethics is that a child's autonomy should be respected. As physical restraint and sedation deprives the child of autonomy, it should only be contemplated as a last resort

- A child who is 'acting out' and who does not need acute medical or psychiatric care should be discharged from the hospital to a safe environment rather than be restrained

- When physical restraint is required, a coordinated team approach is essential, with roles clearly defined and swift action taken. Staff members should never attempt to restrain the child without the Code response team resource on hand

Management

Alternative means of calming a child

See

Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute management for de-escalation techniques

- Crisis prevention: Anticipate and identify early irritable behaviour (and past history). Involve mental health expertise early for assistance

- Provide a safe 'containing' environment. This includes a confident reassuring approach by staff without added stimuli

- Listen and talk simply and in a calm manner

- Offer planned 'collaborative' sedation (eg ask the child if they would take some oral medication to reduce behavioural distress)

Emergency sedation

See

Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute management

Indications for emergency sedation and physical restraint

- Physical restraint should only be used to facilitate rapidly effective pharmacological treatment

Cautions and contraindications to physical restraint and emergency sedation

- A child who is 'acting out' and who does not need acute medical or psychiatric care should be discharged from the hospital to a safe environment (home, police, child protective care) rather than be restrained

- Be aware of previous medications and possible substance use

- Safe containment is possible via alternative means (including voluntary, collaborative oral sedation)

- Inadequate personnel/unsafe setting/inadequate equipment

- Situation judged as too dangerous eg the child has a weapon

Consent

- Obtaining consent for any medical procedures including giving sedation and any further intervention should be sought at all times, even in unsafe situations wherever possible

- Consent should be ideally sought from the child and/or guardians

-

Common law recognises that adolescents can give consent if they have capacity

- In an unsafe setting when the child or adolescent is a danger to themselves or others, no consent is necessary but clinicians should be aware of the relevant Mental Health Act in their

jurisdiction (see Additional notes below)

Procedure

- The Code response team should perform this procedure.

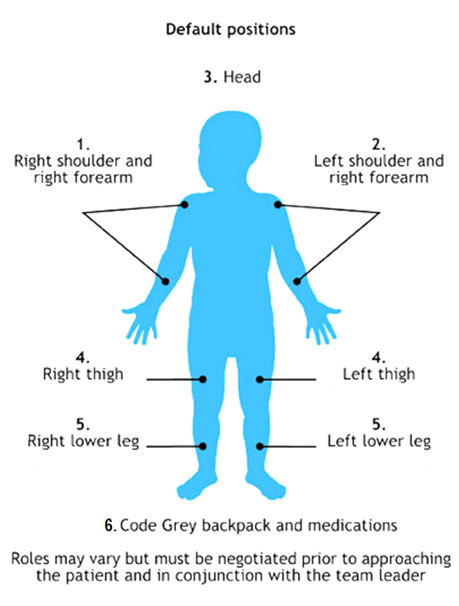

- Team leader will designate roles before approaching child.

- All members should ensure own safety, with gloves and goggles.

- Draw up medication

- Secure the child quickly and calmly using the least possible force. At least five people are required

- The child should be held supine

- Prone positions should be avoided as they are dangerous, causing increased risk of asphyxiation

- Administer the

medications by intramuscular injection into the lateral thigh (other options - ventrogluteal or dorsogluteal). Beware of the risk of needle stick injury. Further titrated doses of medication may be required depending on clinical response (If medication can be given IV this may be an option if the child is safe to cannulate)

- Post sedation care (see below)

- A child who has needed emergency restraint and sedation may also require mechanical restraint in extremely rare circumstances. Not all emergency departments support this practice. It should not occur without specialist mental health input and presence

Figure: Code response procedure

Post-sedation monitoring

See

Acute behavioural disturbance: Acute management

Complications of physical restraints include:

- pressure effects of physical restraints

- complications of being held supine: respiratory depression, risk of asphyxiation, inability to clear vomitus from airway

Ongoing care

- Following restraint, the child must undergo a detailed medical and mental health assessment to guide subsequent management

- In some cases, recommendation and transfer to an inpatient mental health facility may be required

- The need for sedation should be reviewed on an ongoing basis and the child should be cared for in the least restrictive modality so as to provide safety

- Physical restraints should be used only for administration of medication

- As the sedation wears off, the child's risk status should be carefully monitored throughout the entire process

Documentation

Document fully in the child's medical record and medication chart when appropriate:

- the child's response to sedation and complications thereof

- on-going observations documented at least 15 minutely

- time and length of physical restrain when giving medication

- there may be a specific code response reporting form

Defusing and debriefing

- The need to physically restrain a behaviourally distressed child can be extremely distressing for staff involved

- A critical incident stress debriefing session may be required

- It is ideally chaired by an objective facilitator who was not involved in the restraint process. See your health service’s Human Resources Employee Assistance Program (EAP)

Consider consultation with local paediatric team when

- Children require ongoing observation or stabilisation of an underlying medical cause eg resolution of drug toxicity

- Local mental health clinicians are involved in the ongoing care of behaviourally distressed children

Consider transfer when

- The behavioural disturbance is reduced, some children will require transfer to a tertiary mental health facility

- There are complications from sedation

- Child requires care beyond the comfort level of the hospital

For emergency advice and paediatric or neonatal ICU transfers, see

Retrieval Services

Additional notes

Interstate guides to informed consent and the Mental Health Acts

NSW

Mental Health Act 2007 No 8

Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 No 157

Queensland

About the Mental Health Act 2016 – Queensland Health

Guide to Informed Decision-making in Health Care 2nd Edition – Queensland Health

Victoria

Mental Health Act 2014

Informed consent

Restraint in Mental Health Acts Across Australia

Restraint in Australian and New Zealand Mental Health Acts

Last updated September 2020