1. Summary

Many children and adolescents present to Emergency Departments after an acute knee injury, e.g. from a twisting injury during sports, a sudden change in direction, landing a jump, or from a direct blow to the knee.

The challenge for the treating clinician is to differentiate between serious knee injuries and self-limiting conditions in the acute presentation, determining which of these children have a significant internal joint derangement. The most important of these are ligamentous injuries, meniscal tears, and osteochondral fractures. (

Patella Dislocations are covered in a separate guideline, but be aware they may not be appreciated if they have spontaneously reduced).

Pain and swelling associated with the injury can mean it is often not possible to adequately examine the knee, even with good analgesia. Thus, making an accurate diagnosis may be difficult on that day. Excluding a fracture requiring urgent intervention needs to be done but arranging appropriate discharge advice and follow-up is more important than establishing a precise diagnosis.

Decisions about operative intervention are usually best delayed until the acute phase/haemarthrosis has settled, with a few important exceptions discussed below.

Please note that penetrating or open wounds involving the knee are beyond the scope of this guideline

2. Classification, Frequency and Mechanism

Type of internal knee derangement |

Frequency |

Usual mechanism |

|

Anterior cruciate ligament tear (partial or complete) |

Most important in the adolescent age group.

Uncommon under age 10. |

“Pop” heard and giving way of the knee associated with a pivoting movementor knee hyperextension. |

|

Tibial spine avulsion |

Most common in ages 8-15 |

As with ACL, but the ligament remains intact with avulsion of bone at its tibial insertion |

|

Patella Dislocation-reduction

(+/- associated osteochondral fracture)

See separate guideline |

Common |

Valgus force with some femur rotation or direct blow to the medial patella |

|

Meniscus injury (lateral or medial) |

Frequently associated with ligamentous injuries. Anatomic predisposition in some children |

Twisting/Pivoting injury on a weight-bearing, semi-flexed knee. |

|

True Knee Dislocation |

Rare.

Invariably involves multi-ligamentous injury, often with associated vascular and neurological injury |

Major trauma, eg motor vehicle accident or skiing |

|

Posterior Cruciate Ligament tear |

Rare |

High force to anterior proximal tibia with the knee flexed; eg from dashboard during a motor-vehicle accident, landing on a flexed knee e.g. rugby |

|

Medial Collateral Ligament injury |

Rare in children

(May be associated with medial meniscus injury) |

Impact causing valgus stress on knee eg being fallen on by another player |

|

Lateral Collateral Ligament |

Rare in children |

Impact causing varus stress on knee. |

3. Clinical Findings

The knee examination is best performed after adequate analgesia has been arranged – which may include opioids or nitrous. The joint should be examined for deformity, swelling (in particular, the presence of an effusion), and focal tenderness.

When significant joint derangement has occurred, it is often soon followed by a combination of swelling, bleeding into the joint and muscle spasms that can make the joint very painful to move, rendering weightbearing intolerable.

Any examination involving movement of the joint or testing individual structures should occur within the limits of patient comfort.

As the initial treatment of suspected ligamentous/meniscal injury is common to all these injuries, it is not critical that a precise anatomical diagnosis is made on the day of injury. Relief of the patient’s pain and arranging appropriate discharge advice are higher-order priorities. |

When a patient is able to tolerate an examination (which may be several days later), the characteristic findings are as follows:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury: Globally reduced range of motion, usually with effusion and inability to fully extend the knee. Positive Anterior Draw and Lachman’s test with loss of “hard” endpoint on anterior translation of the tibia on the femur. Sensation of “wobbliness” or instability when pivoting. In both the anterior drawer and Lachman’s test, the tibia will slide forward relative to the femur. An endpoint can be found to this sliding in a partial tear of the ligament, but not in a complete tear. Comparison to the uninjured side is helpful when assessing for subtle laxity and gauging where the endpoint should be.

- Tibial Spine Avulsion: Clinical findings are the same as in ACL injury, but can also present with a marked flexed posture and loss of extension due to bony impingement in the femoral notch

- Meniscal injuries (lateral or medial): Globally reduced range of motion with clicking or locking. Pain to palpation along tibial joint lines and positive McMurray’s test. A bucket-handle patterned tear that is flipped can hinder weight bearing and even present with an acutely locked knee with no range at all

- Medial Collateral Ligament injury is suggested by focal tenderness on the joint line directly over the ligament. Flexing the knee to 30 degrees, a valgus stress is applied: laxity or increased pain compared with the uninjured knee suggests an injury to the ligament

- Lateral Collateral Ligament injury: Laxity on varus stress at 30 degrees flexion

Posterior Cruciate Ligament injury: Posterior sag of the tibia in relation to the femur at 90° of flexion. Loss of “hard” endpoint with posterior draw of the knee.

True Knee Dislocation: Gross deformity, often with co-existing vascular or neurological injuries. Represents a surgical emergency that requires prompt investigation and stabilisation.

- Patella Dislocation: If spontaneously reduced, there is still usually significant joint swelling, tenderness to the medial patellar facet or over the lateral femoral condyle;

see Patella Dislocation guideline. There may be a positive patella apprehension sign.

-

- Patella rupture/Patella tendon avulsion/tibial tuberosity avulsion: Significant swelling at the site of the injury, and inability to actively extend knee or raise a straight leg. Or inability to hold the leg in extension against gravity.

4. X-Ray Appearance

X-rays should be ordered in all patients with a haemarthrosis, or an inability to weightbear. Not all knee injuries need an x-ray.

In an isolated anterior cruciate or meniscus injury, often the only X-ray finding is a haemarthrosis in the knee joint.

Figure 1. Moderate haemarthrosis as only radiographic finding in ACL tear

A Segond fracture is an avulsion off the lateral aspect of the tibia. Whilst appearing innocuous to the untrained eye, it represents a menisco-capsular injury that is almost always associated with an ACL injury.

Figure 2 : Coexisting Segond fracture and tibial spine avulsion.

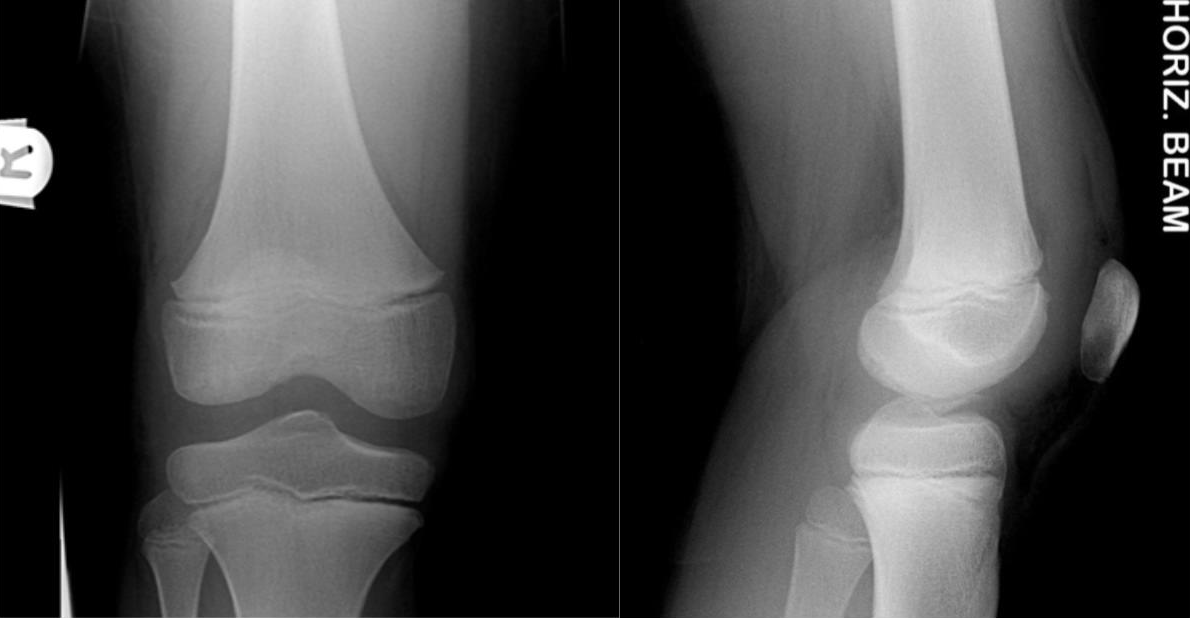

Tibial spine fractures represent avulsion injuries of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament and can be thought of as the paediatric equivalent of an Adult ACL rupture. This fracture can be missed on an AP film and only visible on the lateral Xray

Figure 3: AP and lateral views showing tibial spine avulsion

Figure 4: Acute osteochondral defect – requires admission and arthoscopic removal

5. Emergency Department Management

Early Analgesia provision

Any high-force injuries (eg. Motor Vehicle Accident, water-skiing) require a full

trauma survey for co-existing injuries

Admission on day of presentation for management of any of these injuries:

- True Knee Dislocation (urgent)

- Tibial Spine Avulsion

- Osteochondral Defect (or other loose body)

- Highly unstable knee

- Segond fracture warrants same-day orthopaedic consultation +/- admission

|

(Other injuries where internal joint derangement is suspected are suitable for outpatient management so long as the importance of appropriate follow-up (see below) is understood.)

- Compression is useful early, for example with a double tubular-compression bandage.

- Use of a Knee extension splint (“zimmer”) is controversial. It can aid with analgesia and help minimise knee flexion contractures, but if the child is unable to fully extend the knee this type of immobilisation may be more painful and tends to slip.

-

Crutches will generally be necessary as patients often cannot bear weight acutely.

- Regular ice application at home; for example, 15 minutes 3 times a day for 3 days to the front of the knee.

- Ongoing regular analgesia plan

6. Appropriate Follow-up

Injuries requiring same day admission are listed in point 5 above.

Follow-up is highly important for knee injuries with a significant effusion or where internal joint derangement cannot be excluded at first encounter. This is best done with the family’s GP in the next 1-2 weeks after a period of rest/elevation/intermittent ice.

Re-examination at this appointment is the core aim, as the findings listed in section 3 above will become more apparent once the acute swelling has settled.

The GP will be able to arrange further investigations (including an outpatient MRI (medicare rebate applicable) if there are any persisting signs suggestive of internal joint derangement.

Referral to outpatient orthopaedics and/or physiotherapy can occur depending on the clinical exam and MRI findings.

- Orthopaedic outpatient review should occur in all cases of ACL ruptures, meniscal injuries and osteochondral fractures

- Physiotherapy treatment for these injuries should occur in parallel, in order to recover the range of motion of the knee, prevent quadriceps and hamstring muscle wasting, and work on proprioception.

- Isolated medial collateral ligament injuries can usually be treated with physiotherapy alone +/- hinged knee brace.

Occasionally a family will present to the Emergency Department with a completed MRI demonstrating an ACL injury. This may be driven by a misunderstanding that earlier surgery results in better clinical outcomes.

The priority is restoration of knee range of motion with closed kinetic chain physiotherapy guided injury rehabilitation focusing on quadriceps proprioception and eccentric hamstring exercises. Prompt Orthopaedic referral facilitates consultation in a timely manner- at RCH this is via an orthopaedics clinic referral marked as “urgent”. |

7. Operative Management

Tibial spine fractures may require early surgical fixation in order to prevent malunion of the fragment

True Knee Dislocation will require emergent reduction and treatment of any vascular injuries, with delayed definitive ligamentous repair

ACL Tears: Decisions around reconstruction of these should only be made after expert orthopaedic assessment, often following a period of prehabilitation with physiotherapy. Most partial tears respond to non-operative management through physiotherapy guided injury rehabilitation. Complete ACL tears in skeletally immature patients require special techniques to avoid injuries to the physes and may best be treated when nearing skeletal maturity.

Meniscal tears may require operative treatment, depending on the location and pattern of the injury. Surgical treatment is more likely to be necessary where the knee is locking, catching or giving way.

8. Advice for Parents

- Importance of regular analgesia, ice, compression and initial rest as outlined above

- Swelling is almost ubiquitous, and should not be expected to disappear quickly

- Early physiotherapy input (after the first week) is encouraged

- Patients should avoid twisting or jumping activities, but are allowed to walk when able

- The importance of follow-up with GP at 1-2 weeks post-injury should be conveyed, for re-examination. Medicare rebatable MRI can be arranged from there if joint derangement suspected.

9. Potential complications

ACL injury: possibility of ongoing knee stability without treatment; possibility of osteoarthritis in the long term (whether reconstruction undertaken or not)

Meniscus injury: ongoing instability and pain

True knee dislocation: associated neurovascular injuries and/or compartment syndrome

All injuries: possibility of significant muscle atrophy (particularly VMO) if early physiotherapy/mobilisation is not undertaken, flexion contractures

10. References

Fabricant, P. & Kocher, M. Management of ACL Injuries in Children and Adolescents, J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2017;99:600-612

Ardern C et al, International Olympic Committee consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of paediatric anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(4):989-1010

Shieh, Meniscus Tear Patterns in relation to skeletal immaturity: Children vs Adolescents Am J Sports Med 2013;41(12)2779-83

Mathison D. & Teach S. Approach to Knee Effusions, Pediatric Emergency Care 2009;25(11):773-86