Fracture Guideline IndexSee also: Humeral shaft fractures - Fracture clinics

- Summary

- How are they classified?

- How common are they and how do they occur?

- What do they look like - clinically?

- What radiological investigations should be ordered?

- What do they look like on x-ray?

- When is reduction (non operative and operative) required?

- Do I need to refer to orthopaedics now?

- What is the usual ED management for this fracture?

- What follow-up is required?

- What advice should I give to parents?

- What are the potential complications associated with this injury?

1. Summary

Reduction is seldom required for humeral shaft fractures.

Fractures will usually "hang out" (i.e. under influence of gravity) to good alignment and apposition using a collar and cuff. Mid-shaft humeral fractures should be followed up in fracture clinic at 1 week.

Spiral fractures of the humerus in toddler age and younger are strongly linked with non-accidental injury. Careful history and examination are required to determine the child at risk.

2. How are they classified?

Humeral shaft (diaphyseal) fractures can be classified by

- Anatomical location: proximal, middle or distal third

- Fracture pattern: spiral, short oblique, transverse or comminuted

- Degree of displacement

- Presence of soft tissue damage (open or closed)

3. How common are they and how do they occur?

These fractures are uncommon and account for 2-5% of all fractures in children.

Transverse and short oblique fractures are generally as a result from direct trauma, whereas spiral fractures are caused by indirect twisting, as with a fall.

Pathological fractures through a humeral simple bone cyst are relatively common after minimal trauma in children over 7 years old.

Humeral shaft fractures are the second most common birth fracture. Humeral shaft fractures in children under four years should lead the examiner to be alert for other signs of non-accidental injury. This fracture is a hallmark of non-accidental injury.

Spiral fractures of the humerus in infants and toddlers are strongly linked with non-accidental injury. Careful history and examination are required to determine the child at risk.

4. What do they look like - clinically?

The arm is usually swollen and tender and the child will be unwilling to move the arm. Crepitus may be present. Deformity may not be obvious due to swelling and the dependency of the arm.

Radial nerve palsy can occur with a fracture at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the shaft. There will be loss of finger metacarpophalangeal (MCP) extension and loss of wrist extension. Sensory loss will be in the dorsum of the 1st web space.

5. What radiological investigations should be ordered?

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the humerus should be ordered.

6. What do they look like on x-ray?

Fractures of the humeral shaft are often either transverse fractures or spiral. Look for evidence of bone cysts or other pathologic fractures.

Transverse fracture through humerus

Figure 1: Six year old boy with a transverse fracture of the shaft of the humerus.

7. When is reduction (non-operative and operative) required?

Reduction is seldom required. Fractures will usually "hang out" (i.e. under the influence of gravity) to good alignment and apposition using a collar and cuff. This allows the weight of the arm itself to act as traction across the fracture.

Parameters for acceptable alignment are:

- Axial alignment within 10 degrees - assessed on imaging

8. Do I need to refer to orthopaedics now?

Indications for prompt consultation include:

- Open fractures

- Neurovascular injury with fracture (radial nerve palsy)

- Extreme swelling/compartment syndrome - extremely rare with humeral fractures

- Unable to achieve or maintain reduction (including if ED is not experienced in fracture reduction, splinting or casting)

- Pathological fracture

Acute referral is needed if neurological signs have occurred after manipulation of the fracture, as this may indicate the radial nerve has become entrapped.9. What is the usual ED management for this fracture?

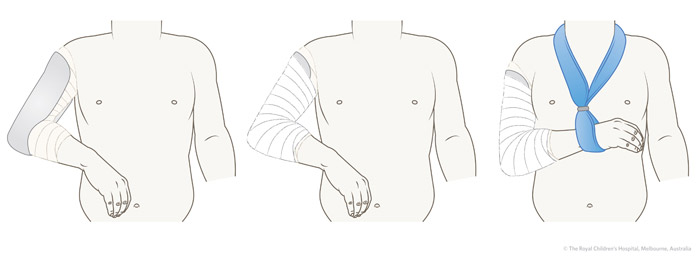

Middle third fractures of the humeral shaft are managed with a collar and cuff. Occasionally a hanging U-slab plaster of Paris (POP) is required (Figure 2). If a radial nerve injury is present, active manipulation is not recommended. These injuries usually recover spontaneously and treatment is supportive with wrist and dynamic finger splintage.

Figure 2: Hanging U-slab plaster of Paris

10. What follow-up is required?

Humeral shaft fractures should be referred to fracture clinic at 1 week.

Minimally displaced fractures can be handled by experienced GPs after appropriate handover.

If there is any concern as to the nature of the fracture, orthopaedic referral at presentation should be sought.

11. What advice should I give to parents?

Pain from the fracture and restriction of movement are usual for 2-3 weeks and will require regular analgesia. The child will feel more comfortable if they sleep propped up in bed.

Follow-up is important with an x-ray at one week to ensure adequate maintenance of position and neurological function.

Healing generally takes 4-6 weeks depending on the age of the child, to reach a point when active mobilisation will be commenced. Family should be advised to re-attend if pain is increasing, or sensation changes abruptly.

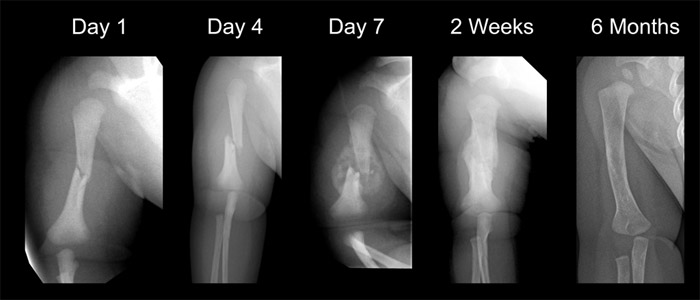

Well aligned humeral shaft fractures in children heal reliably. Strong periosteal healing and remodeling usually result in excellent function and cosmesis (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Young children have excellent remodelling potential. These are sequential radiographs of a child who sustained a fracture of the midshaft of the right humerus during birth. Note the very rapid healing with extensive callus by day 7 followed by remodelling.

12. What are the potential complications associated with this injury?

Radial nerve injury is uncommon. These injuries usually recover spontaneously and treatment is supportive with wrist and dynamic finger splintage.

See fracture clinics for other potential complications.

References (ED setting)

Herring JA. Upper extremity injuries. In Tachdjian's Pediatric Orthopedics, 4th Ed. Saunders, Philadelphia 2008. p.2441-50.

Hunter JB. Fractures around the shoulder and humerus. In Children's Orthopaedics and Fractures, 3rd Ed. Benson M, Fixsen J, Macnicol M, Parsch K (Eds). Springer, London 2010. p.717-30.

Mooney JF, Webb LX. Fractures and dislocations about the shoulder. In Green and Swiontkowski: Skeletal Trauma in Children, 4th Ed. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia 2008. p.283-311.

Sarwark J, King E, Janicki J. Proximal humerus, clavicle and scapula. In Rockwood and Wilkins' Fractures in Children, 7th Ed. Beaty JH, Kasser JR (Eds). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2010. p.620-81.

Feedback

Content developed by Victorian Paediatric Orthopaedic Network. To provide feedback, please email rch.orthopaedics@rch.org.au