Table of contents will be automatically generated here...

Introduction

Significant chest injury is

rare in paediatric trauma. Most cases

occur secondary to blunt chest trauma, with penetrating injuries accounting for

less than 10% or the total reported incidence worldwide.

Over a 5 year period to 2007

there were 204 cases of severe paediatric thoracic trauma in Victoria1. The most common injuries identified were

lung contusion (65%) and haemo/pneumothorax (37%). Blunt trauma accounted for 96% of injuries

and 75% were secondary to motor vehicle accidents (including pedestrian vs motor vehicle). Due to this frequent association

with motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) patients with chest trauma usually have concomitant injuries to other

major systems, most commonly the head and abdomen. In the above study 99% of patients had an

injury to one of more other body regions.

This underscores the high level of force involved in most paediatric

chest trauma.

Mortality

Mortality in children with

chest trauma has been quoted to be as high as 30% although death is not always

related directly to the chest injury. Death usually occurs soon

after the injury in a child, whereas an adult with comparable injuries tends to

survive longer.

How children are different

- A major difference between adults and children is the compliance of the chest wall, due to the greater elasticity of the ribs. This allows greater deformation of the chest wall before the ribs fracture. Thus major internal injuries may occur without any

external chest wall injury.

- Children have a greater cardiopulmonary reserve, and so compensatory mechanisms may mask hypovolaemia and respiratory distress.

- A drop in blood pressure in the paediatric population is a very late sign, signifying imminent death.

- The mobility of the mediastinum decreases the risk of major airway and vessel injury. However, ventilatory and cardiovascular compromise may occur rapidly, due to the mediastinal shift.

- A common response to injury in children is aerophagia, which is often associated with a reflex ileus. This can lead to acute gastric dilatation, which may further compromise respiratory function.

- There should be a high index in paediatric trauma for orogastric / nasogastric placement, with orogastric only indicated where head injury is a concern.

In all aspects of trauma

management, the primary survey is first

priority

Primary survey

The purpose of the primary

survey is to identify and manage life threats. The particular thoracic

injuries that are necessary to identify during the primary survey include:

-

Tension

pneumothorax

- Open

pneumothorax

- Massive

haemothorax

- Flail

chest

- Cardiac

tamponade

In these injuries frequent

reassessment of ABC is a necessary part of their assessment & management

Types of injuries

Tension Pneumothorax

- Accumulation

of air in the pleural space under pressure resulting in compression of the

ipsilateral lung

- Progressive

air accumulation causes mediastinal shift and development of compression to the

contralateral lung

- Impaired

venous return

- Compromised

cardiac output

Diagnosis

- Hypoxia

- Severe

respiratory distress

- Altered

level of consciousness

- Shift in

mediastinum or trachea to the contralateral side

- Distended

neck veins

- Absent

or decreased breath sounds bilaterally

- Hyper-resonance

to percussion

- Impaired

venous return to the heart

- Patient

will be tachycardic with peripheral vasoconstriction and in hypotensive shock

Treatment

(see also Management of Traumatic Pneumothorax and Haemothorax)

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

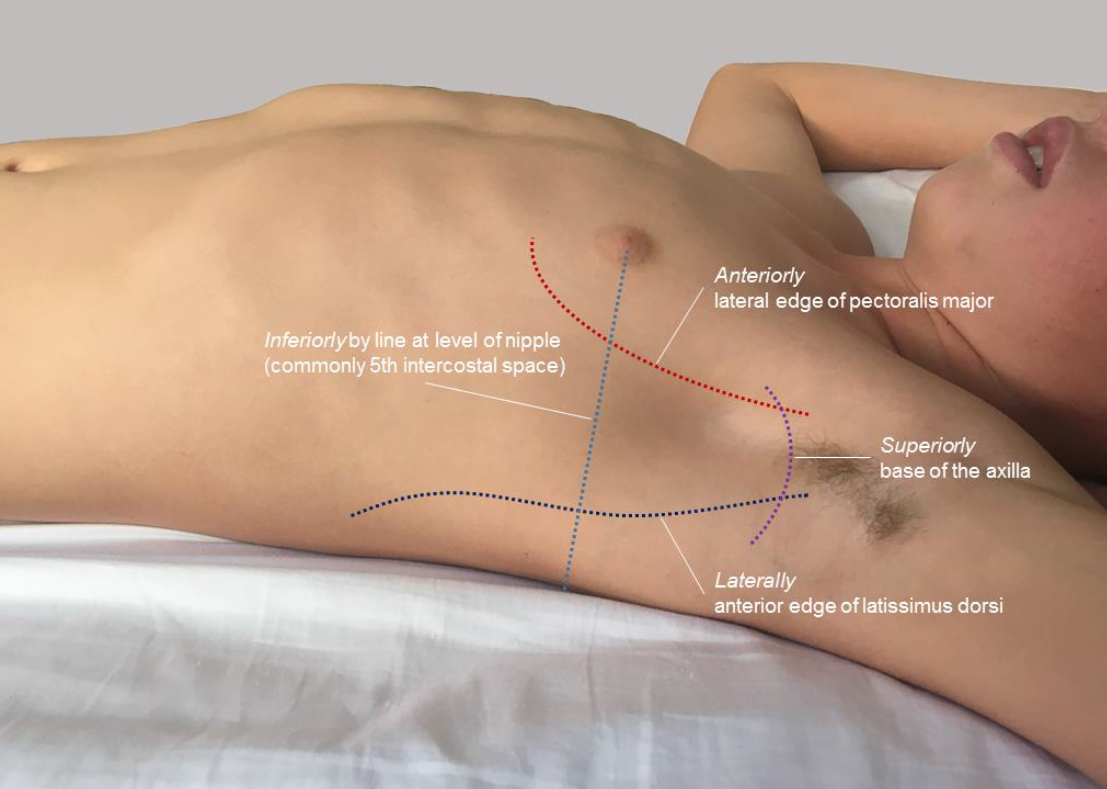

- Immediate finger thoracostomy is the preferred management in the in-hospital environement. This is done in the 4th or 5th intercostal space, between the anterior and mid-axillary line, on the side of the pneumothorax, followed immediately by an intercostal catheter in the same location (Figure 1).

- If unable to do an immediate finger thoracostomy, an immediate needle thoracocentesis – midclavicular line, 2nd intercostal space,

on the side of the pneumothorax (Figure 2 & 3). This should be followed as soon as possible by a finger thoracostomy and intercostal catheter insertion – 4th or 5th

intercostal space anterior axillary line

Figure 1 - surface marking for left sided finger thoracostomy and intercostal catheter insertion

Figure 2 – surface marking for needle

thoracocentesis

Figure 3 – needle thoracocentesis insertion

There is a 10-20% chance of causing a

pneumothorax if thoracocentesis is attempted in the absence of a pre-existing

pneumothorax. This procedure must be

followed up by a chest x-ray and insertion of an intercostal catheter.

Open Pneumothorax

- This

injury occurs secondary to penetrating wounds of the chest. It occurs where the wound is greater than two thirds the diameter of the trachea. At this size and above, the negative pressure generated through excursion of the chest in inspiration, will lead to the preferential influx of air via the wound into the pleural space, rather than via the upper airway. If air fails to escape with expiration, a tension pneumothorax will develop.

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Hypoxia

- Decreased

chest movement

- Decreased

air entry

- Hyper-resonant

to percussion

- Chest

wound through which air may be heard passing with inspiration & expiration

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

- In hospital, cover

with occlusive dressing (small wounds) or suture/staple the wound closed (larger wounds)

- Immediate

insertion of intercostal catheter

- The use of a 3 sided occlusive dressing - to act as a one way valve - is no longer recommended as treatment for an open pneumothorax once the patient has arrived in hospital. If may be applied when the patient is being managed in the pre-hsopital environment and there will be a delay to insertion of an intercostal catheter. However, they can be hard to apply to a bleeding wound, and they have variable efficacy.

Figure 4 - A 3 sided occlusive dressing

Massive

Haemothorax

- This is

a rare injury in the paediatric population

- Rapid,

large volume accumulation of blood in the pleural space

- May

result secondary to a blunt or penetrating injury – cardiac or great vessel

injury

- Potential

to lose up to 40% of blood volume in each hemithorax

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Decreased

chest movement

- Decreased

air entry

- Dullness

to percussion

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

- Ventilatory

support

- Rapid

fluid resuscitation

- Insertion

of intercostal catheter – 4th or 5th intercostal space,

anterior axillary line (Figure 1)

- Urgent

surgical review for possible thoracotomy if ongoing haemorrhage with inability

to stabilise circulation despite aggressive fluid resuscitation

Flail Chest

- This occurs secondary

to blunt injury - it is less common in children than in adults due to the greater elastic properties of the paediatric ribcage - which permits far greater plastic deformation on impact without resultant broken ribs. However, the underlying lung parenchyma is susceptible to contusion

- A flail chest is the

result of 2 or more fractures in two or more adjacent ribs interrupting the

bony continuity of the thoracic wall (Figure 5)

Figure 5 – Flail chest with pulmonary

contusions

Diagnosis

- “Paradoxical

movement” – the flail segment is seen to collapse with inspiration and bulge

with expiration while the rest of the chest wall moves in the opposite way

- Respiratory

distress

- Possible

decreased air entry due to associated pulmonary contusion and splinting

- Possible

subcutaneous emphysema

Treatment

- Aggressive

analgesia

- High

flow oxygen with ventilatory support as necessary

- Stabilisation

of flail segment. Patient may be placed

injured side down

- Positive pressure ventilation improve ventilation, and intubation may be necessary to help with analgesic demands.

- Referral to cardiothoracic surgeons for consideration of rib fixation

Cardiac Tamponade

- Bleeding

into the pericardium secondary to blunt or penetrating injury

- Blood

may originate from cardiac chamber, a great vessel or from the myocardium in

the presence of a myocardial contusion

- Results

in decreased filling of the heart and thus reduced stroke volume and shock

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Hypotension

- Narrow

pulse pressure

- Distended

neck veins

- Soft

heart sounds

- Refractory

shock

Investigations

- Bedside

USS for confirmation if time permits

Treatment

- ECG

monitoring

- High

flow oxygen

- Fluid

resuscitation (to increase preload and minimise right ventricular collapse)

- The optimum treatment for a pericardial tamponade secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma is open surgical drainage in theatre.

- In the situation where there is severe shock and no surgical facilities available, needle pericardiocentesis can be performed as a temporising measure.

- A long needle is inserted at a left sub-xiphoid position, and directed posteriorly at a 45° angle and towards the left shoulder - this is better performed under ultrasound guidance where skills and equipment permit.

There is limited evidence for the role of an ED thoracotomy in the paediatric population who have sustained a blunt injury, it should be considered in the event of penetrating trauma

Pulmonary Contusion

- The most

common thoracic injury in children

- Often

associated with other injuries such as fractures and haemothorax

- May

occur in absence of obvious chest wall injury

- Haemorrhage

and oedema within affected lung segment

Diagnosis

- Hypoxia

– degree of compromise will depend on size of contusion

- Respiratory

distress – may very in severity

- Decreased

air entry on ipsilateral side

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – patchy consolidation, may be bilateral (Figure 5) - may initially be unremarkable with changes

evolving over 24-72 hours

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

- Pulmonary

toilet including regular suction and chest physiotherapy

- Ventilatory

support

- Contusions

may evolve clinically & radiologically over first 24-72 hours

Rib Fractures

- The

paediatric chest wall can sustain more deformation before rib fractures occur

compared with the adult chest wall

- Despite

this rib fractures are still common in paediatric chest trauma

- Indicative

of significant injury and greater likelihood of comcommitant multisystem

injuries

- Almost always

associated with pulmonary contusions

Diagnosis

- Chest

wall bruising/abrasions

- Respiratory

distress

- Hypoventilation

secondary to splinting

- Decreased

chest expansion

- Hyper-resonance

or dullness to percussion (depending on associated pneumothorax or contusion)

- Normal

or decreased air entry

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – fractures & consolidation may be evident - may be

unremarkable initially

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Aggressive

analgesia

- Ventilator

support as necessary

- Inpatient

monitoring as deterioration may occur due to associated pulmonary contusions

Simple Pneumothorax

- Accumulation

of air in the pleural space

- Degree

of compromise related to the size of the pneumothorax and other associated

injuries

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Pleuritic

chest pain

- Decreased

chest wall movement ipsilateral side

- Decreased

air entry

- Ipsilateral

hyper-resonance to percussion

- May be

asymptomatic

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – collapse of lung parenchyma on ipsilateral side with slightly increased

expansion of chest wall

- Ultrasound

– absence of lung sliding and B-lines, presence of A-lines; presence of a lung point. This should be performed

by experienced clinician

Treatment:

- Supplemental

oxygen

- Analgesia

- Ventilatory

support as necessary

- If

patient has respiratory compromise or the pneumothorax is >20% on chest

x-ray insertion of intercostal chest catheter is required

- If the

patient does not meet above criteria and thus doesn’t require immediate chest

drain insertion, admission and intensive monitoring is required as a simple

pneumothorax may enlarge and become symptomatic or even convert to a tension

pneumothorax

Haemo-Pneumothorax

- A

combination of the accumulation of both blood and air in the pleural space

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Decreased

chest wall movement

- Decreased

air entry

- Dullness

to percussion

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – collapse of ipsilateral lung, pleural effusion with air/fluid level in

pleural space

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

- Ventilatory

support as necessary

- Fluid

resuscitation

- Insertion

of intercostal chest drain

Pulmonary Laceration

- Most

commonly secondary to penetrating injury but may occur with blunt trauma

- Typically

associated with pulmonary contusions and haemopneumothorax on the ipsilateral

side

Diagnosis

- Signs of

trauma to chest wall ie. Bruising/abrasions

- Respiratory

distress

- Hypoxia

- Decreased

chest expansion

- Dullness

to percussion

- Decreased

breath sounds

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray - collapse of ipsilateral lung, pleural effusion with air/fluid level in pleural

space

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

- Ventilatory

support as required

- May

require surgical intervention if persisiting air leak or bleeding

Traumatic Rupture of the

Aorta

- Very

rare injury in the paediatric population

- Typically

occurs in rapid deceleration injuries such as that sustained in high-speed

motor vehicle accidents

- Commonly

occurs at, or very close to, the ligamentum arteriosum which attaches to the

proximal descending aorta just beyond the left subclavian artery. The ascending aorta and aortic arch are much

more mobile compared with the descending aorta and it is probable that at the

time of impact a major torsional inury occurs at this junction

- In many

cases this injury will result in immediate massive blood loss into the left pleural

cavity and death occurs at the scene of the accident.

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Decreased

air entry and dullness to percussion on the left

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

If

suspected on plain radiography further investigation is required – CT chest,

aortogram or trans-oesophageal echocardiogram.

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – suspect with any of the following features

- Widened

mediastinum on erect film

- Pleural

cap over the apex of the left lung (due to haemoatoma tracking upwards)

- Loss of

the aortic knuckle

- Deviation

of trachea or oesophagus to the right

- Depression

of left main stem bronchus

- If

diagnosis suspected on plain radiography further investigation required

- CT chest

- Aortogram

(Gold Standard)

- Trans-oesophageal

echocardiogram

Treatment

- Analgesia

- Fluid

resuscitation

- Supplemental

oxygen

- Ventilatory

support as needed

- If

diagnosis confirmed will require aortic surgery to resect the site of injury

with either aortic repair of replacement

Tracheo-Bronchial Injury

- Rare

injury

- Potentially

life threatening

- Almost

exclusively occurs due to penetrating injury

- Results

from trauma to region between larynx and segmental bronchus

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Hypoxia

- Partial

airway obstruction

- Subcutaneous

emphysema

- Decreased

air entry

- Continuous

air leak after insertion of intercostal catheter

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – pneumothorax (may be bilateral), pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous

emphysema

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen – adequate oxygenation may be difficult to achieve

- Analgesia

- ETT

placement beyond level of injury

- Ventilatory

support

- Referral

to thoracic surgeon for definitive management

Oesophageal Injury

- Rare

- Most

commonly due to penetrating injury but may occur following blunt injury to the upper

abdomen causing forceful ejection of stomach contents into the oesophagus

resulting in a linear tear in the lower oesophagus

Diagnosis

- Respiratory

distress

- Fever

may be present

- Subcutaneous

emphysema

- Peritonism

- guarding, rigdity

- Decreased

air entry

- Intercostal

catheter may drain gastric contents

Investigations

- Chest

x-ray – pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, subcutaneous

emphysema

Treatment

- Supplemental

oxygen

- Analgesia

- Insertion

of nasogastric tube

- Broad

spectrum antibiotic cover

- May be

managed conservatively or require insertion of intercostal chest drain

- Surgical

intervention may be required

Myocardial contusion

- Typically

occurs following direct blunt trauma to the sternum

- Most

often involves the anterior wall of the heart

- Should

be suspected in any patient with injury over the sternum, in particular if

there is a sternal fracture

Diagnosis

- Anterior

chest wall bruising/tenderness

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnoea

- Prolonged

capillary refill time

- Hypotension

- May have

arrhythmia

- May be

asymptomatic

- May be

complicated by cardiac tamponade

Investigations

- ECG –

monitor for changes similar to those of myocardial infarction or arrhythmias

- Cardiac

enzymes

- Echocardiogram

to detect impaired myocardial function (dyskinesis or akinesis)

Treatment

- Supplemental

oxygen

- Analgesia

- ECG

monitoring

- Serial

cardiac enzymes

- Follow

up echocardiogram

Diaphragmatic Rupture

- Rare

injury but well recognised

- Occurs

due to forceful blunt abdominal injury causing a sudden, major increase in

intra-abdominal pressure

- Usually

left sided

- May

result in abdominal viscera being displaced into thoracic cavity

Diagnosis

- Tachypnoea

- Possible

hypoxia

- Evidence

of abdominal trauma – contusion/abrasion

- Decreased

chest wall movement

- May have

decreased air entry on left with potential for bowel sounds in chest

- Mediastinal

shift may occur

Investigations

- CXR –

difficult to identify diaphragm, abdominal contents in hemithorax, tip of NGT

in chest (Figure 6 & 7)

- Contrast

study gives definitive diagnosis (Figure 8)

Figure 6 - diagphragmatic rupture, unable to visualise left diaphragm

Figure 7 - diagphragmatic injury, nasogastric tip visible in left hemithorax

Figure 8 - diaphragmatic injury, contrast within stomach visible in left hemithorax

Contrast study or CT will give definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Analgesia

- NGT

placement

- Surgical

referral

Traumatic Asphyxiation (“run

over” injury)

- Very

rare

- Caused

by severe, prolonged compression of the chest

- Results

in obstruction of venous return leading to extravasation of blood into tissues

Diagnosis

- Petechiae

of upper chest, neck, arms and face

- Bulging

eyes

- Subconjunctival

haemorrhages

- Massive

subcutaneous oedema

- Respiratory

distress

- Tachypnoea

- Hypoxia

- Decreased

chest movement

- Decreased

air entry

- Underlying

vascular injury – assess for pulses, bruits, haematomas, intracranial

haemorrhage

- Underlying

nerve injury – assess for motor and sensory deficits

Treatment

- High

flow oxygen

- Intubation

and ventilator support

- Analgesia

- Management

must be directed to underlying injuries

- Referral

to thoracic surgeon

IMAGING

Chest X-ray

- Good

screening tool

- Limited

in trauma assessment as images are taken with patient supine and therefore more

difficult to appreciate certain injuries ie. Pneumothorax, Hamothorax

- Consider

cross-table film to better assess for these injuries

- Useful

guide for selective CT imaging

- Normal

chest x-ray essentially excludes significant thoracic injury requiring

intervention2,3,4

CT Chest

- Not

routine in paediatric trauma

- Selective

use in cases with abnormal chest x-ray or high clinical suspicion

- Radiation

exposure is approximately 6x that of plain radiography and increases lifetime

risk of malignancy to 1/500 and risk of fatal malignancy up to 1/12002,3

- Injuries

picked up on chest CT with normal x-ray most commonly rib fractures or

pneumothorax, usually not of clinical significance and not requiring

intervention2,3,4.

- Therefore

radiation risk versus clinical benefit too high2,4

Chest Ultrasound

- Can be

useful in detection of pneumothorax and haemothorax that may not be evident on

supine chest x-ray4 .

- More

sensitive in diagnosing pneumothorax than plain chest x-ray in the hands of an

experienced clinician

- FAST and

EFAST not validated in the paediatric population

Resuscitative thoracotomy

- Resuscitative thoracotomy in the Emergency Department, in traumatic cardiac arrest, is controversial in

paediatrics. However it is an accepted procedure in adult trauma management.

- Given

the rarity of severe chest trauma in children the literature of resuscitative thoracotomy, in the paediatric population, is scarce

- Studies

investigating efficacy of emergency department thoracotomies in children have

demonstrated some success in older children, primarily teenagers, with

penetrating chest trauma who have detectable signs of life at the scene of

trauma5,6,7,8

- There

have only been 2 patients documented in the literature who have survived ED

thoracotomy following blunt chest trauma, these were in 1988 & 19896,7

- There

has been no survival documented in the literature of children under 9 years of

age who underwent emergency department thorocotomy6,7

- However

given that the alternative is death, most studies suggest that in selected cases

ie. older children who fit the above criteria (penetrating chest trauma with

signs of life at the scene) resuscitative thoracotomy be considered5,8 (This is reliant on sufficient training and expertise existing, as well as the ongoing capability to provide thoracic surgical expertise to the patient).

- A recent consensus based guideline developed by the PERUKI group has been developed9. This looked at traumatic paediatric cardiac arrest that was not due to hypoxia (e.g. drowning, asphyxiation or imapact apnoea), and recommended the provision of specific lifesaving interventions over the use of chest compressions and defibrillation. The lifesaving interventions recommended are:

- external haemorrhage control,

- adequate oxygenation and ventilation,

- bilateral thoracostomies,

- rapid volume replacement with warmed blood and blood products and,

- application of a pelvic binder

Summary

- A lack of external signs does not preclude

major underlying thoracic injury

- Chest injuries rarely occur in isolation,

usually being associated with injury to other systems, most commonly head or

abdomen

- Physiological differences of the paediatric

chest must be taken into consideration – especially during the primary and

secondary survey

- Treatment in the absence of major

cardiovascular or tracheobronchial injury will be guided by oxygenation. In many cases, the use of adequate analgesia

and supplemental oxygen may be all that is needed

- The insertion of intercostal catheters should

be considered in the following cases10

- Where there is an intrapleural collection

causing compromise

- Where there is a significant chest injury and

the patient is to be placed on positive pressure ventilation

- Where the patient is to be transported by air

ambulance

References

- Samarasekera

SP, Mikocka-Walus A, Butt W, Cameron P.

Epidemiology of major paediatric chest trauma. J of

Paediatrics and Child Health. 2009; 45: 676-680

- Holscher

CM, Faulk LW, Moore EE et al. Chest

computed tomography imaging for blunt pediatric trauma: not worth the radiation

risk. J of Surgical Research.

2013; 184: 352-357

- Yanchar

NL, Woo K, Brennan M, et al. Chest x-ray

as a screening tool for blunt thoracic trauma in children. J

Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 75: 613-619

- Moore

MA, Wallace EC, Westra SJ. Chest Trauma

in Children: Current Imaging Guidelines

and Techniques. Radiol Clin N Am. 2011; 49: 949-968

- Easter

JS, Vinton DT, Haukoos JS. Emergent

pediatric thoracotomy following traumatic arrest. Resuscitation. 2012; 83:

1521-1524

- Allen CJ,

Valle EJ, Thorson CM, et al. Pediatric

emergency department thoracotomy: A

large case series and systematic review.

J of Pediatric Surgery. 2015; 50:

177-181

- Flynn-O’Brien

KT, Stewart BT, Fallat ME, et al.

Mortality after emergency department thoracotomy for pediatric blunt

trauma: Analysis of the National Trauma

Data Bank 2007-2012. J of Pediatric Surgery. 2016; 51:

163-167

- Moore

HB, Moore EE, Bensard DD. Pediatric

Emergency Department Thoracotomy: A

40-Year Review. J of Pediatric Surgery.

2016; 51: 315-318

- Vasallo, J., Nutbeam, T., Rickard, AC. et al. Paediatric traumatic cardiac arrest: the development of an algorithm to guide recognition, management and decisions to terminate resuscitation. Emer Med J. 2018; 35:669-674

- Strutt

J, Kharbanda A. Pediatric Chest Tubes

And Pigtails: An Evidence-Based Approach

To The Management Of Pleural Space Diseases.

Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Practice. 2015; 12: 1-24